April 2025 Reading Review

Marilynne Robinson, Gene Wolfe, Isabella Hammad, Chloe Dalton

Today’s post is too long for email, so please do click through to your browser or the app to read in full.

Welcome to one of my reading round-up posts, where I take stock and review everything I read over the course of the last month! I read widely across many genres, with a particular focus on literary and speculative fiction alongside some classics (and the occasional dose of nonfiction, too). With these I’m hoping to shed some light on backlist gems, perhaps push you to read outside your genre comfort zone, and also highlight which new releases are worth your time.

Every few months I make a commitment to picking up a book instead of my phone as often as possible, and every few months I have to refresh this commitment when I find myself slipping back into my old scrolling ways. I’m not even that mad about this cycle; I feel like every time I start it again I have scrolled a little bit less to get there, so maybe eventually it will be more or less broken for good. Anyway, April was one of those months where I renewed my commitment to reading more and scrolling less, and it shows in the volume of reading material.

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson (1980)

Like much of my reading at the moment, this was a re-read. This is the Year of the Re-Read for me so far and I’m loving it! (Though it would have been helpful if all my books weren’t packed away in boxes…) Anyway, it’s been so long since I first reviewed it I think it absolutely deserves an update.

I first read this at at university, and I remember loving it. When I read Gilead years later, I was surprised the same author had written both novels, as I felt it didn’t really match up to the Robinson I thought I knew. Now that I’ve re-read Housekeeping, I feel there are more similarities than I thought—biblical allusions still abound—but there is something intense about Housekeeping that does seem to be the marker of a younger and more passionate version of Robinson.

The book is narrated by Ruth, a young girl living with her sister in Idaho and haphazardly cared for by a stream of women. First, their mother abandons them on her own mother’s porch; then they are tended to by said grandmother who is caring but absent emotionally; upon her death some elderly aunts take over to disastrous effect; and finally they are left in the care of Sylvie, their strange and flighty aunt. Ruth takes to Sylvie instantly, clearly desperate for some sort of care and stability, even if it comes in the form of a woman who has for most of her adult life been a “transient” (cue gasp from respectable ladies… I believe this is supposed to be set during the 50s). Her sister, meanwhile, repudiates Sylvie’s lifestyle (and Ruth in turn), abandoning them both for a more conventional life.

I had remembered the novel as a mostly realistic coming-of-age tale that remarks on the relationship between femininity, motherhood and the home. Certainly parts of the novel do speak to this, and the first half is generally rooted in realism. But I was totally unprepared for how utterly strange this novel is, particularly in that second half, and also how desperately sad. Ruth as narrator will not appeal to everyone. She is oddly detached and sometimes feels under characterised, and yet I read this as indicative of her deep and lasting trauma. She does occasionally enter these extremely heightened states of emotion in the novel which were sometimes difficult to parse at a sentence level (we read this for book club and so read it especially closely—very rewarding!) but when you had untangle their meaning, felt deeply poignant and really quite upsetting. As a portrait of an abandoned child, it is entirely damning to all those who fail Ruth. These rapturous moments that come more and more often as we get deeper into the novel push well beyond the boundaries of normal literary realism, feeling surreal and blending folkloric and biblical imagery to great and piercing effect.

I don’t think this novel will appeal to all. This shift in tone feels odd and even uncomfortable. But for me I think it makes it a minor masterpiece. It is incredibly ambitious and filled with a real depth of feeling that is so hard to achieve (especially in this page count), and it did indeed signify the appearance of a future literary giant. One I will continue to return to, I think.

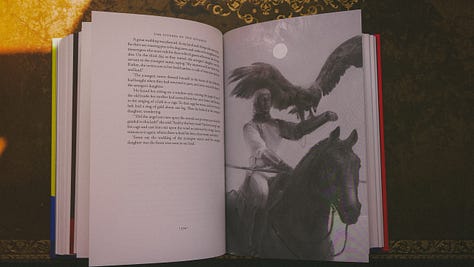

The Sword and the Lictor and The Citadel of the Autarch by Gene Wolfe (1982, 1983)

I finally finished Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun! This is elevated speculative fiction from the 80s and the series (made up of four volumes) is regarded as a bit of a classic. Le Guin famously called Wolfe “our Melville”. Last year I read the first two books in which we are introduced to Severian, our narrator and protagonist. They’re set in the far distant future—mankind has already gone to space and back again, and lives out its last remaining years under the dying sun weighed down by the arcane customs of thousands of years of history, distorted by the passage of time. Much of the powerful technological and scientific knowledge we once possessed has been lost, meaning at times the narrative has the feel of fantasy rather than science fiction, as the characters use more analogue tools and accoutrements from the deep past, while sometimes encountering advanced technology they have no words to describe (i.e. magic).

Severian is raised in a guild of torturers, which is whatever passes in this world (nation?) for a justice system. It is as unnerving a childhood as you might imagine, but is unremarkable to him in many ways. However, when he shows a sign of mercy to one of the “clients” of the guild, he is sent away to live out his life on the periphery of power, in a faraway city named Thrax. When we get to the third volume, he has finally made it to this posting after a long, strange journey, and has taken up his role there as executioner. Of course, his journey is far from over, and his tendency to mercy—especially toward beautiful women—hasn’t left him yet.

These books are much loved and much lauded within the genre, and there are many things to like about them. Wolfe’s prose is often beautiful—his imagery is vivid and evocative, and there are striking passages throughout. Over the course of the book(s), his prowess at a sentence level bolsters and deepens his world-building (though occasionally his wont for an obscure archaic word or turn of phrase gets in the way unnecessarily). Peering through Severian into this world feels like peering into something with great depth and dimensionality. Wolfe is up there with the best in this regard. I could feel and see and imagine the accretions of thousands of years of human culture writ on the planet’s landscape. I felt the vastness of the space given over to this world in Wolfe’s mind.

For the most part I enjoyed following Severian on his meandering journey, never quite knowing where he would go next, and who he would encounter. The singularity of Wolfe’s vision meant there was much there to surprise and delight, and that felt fresh and original. Where speculative fiction can get trope-y quickly, this is always welcome.

But there was something missing for me. Even though I admired them quite a lot and even enjoyed much of my time with them, I could never quite fall in love. These novels are well known for presenting the reader with a bit of a puzzle. Severian is your classic unreliable narrator, and from my reading of various introductions and reviews, I understood that the reader is supposed to pick up on clues throughout the narrative to build a fuller picture of the subtext of the book, or determine the parts that are left unresolved on the surface. Loving puzzling novels as I do, I looked forward to this challenge. But by the time I reached the end, I was left a little cold.

I wonder how I would have felt if I hadn’t approached it in this way at all. Because whilst there is most definitely some joy to be found at piecing together parts of the novel(s) to give you a better understanding of what, exactly, is actually going on, it’s not like there is a grand reveal that changes the way you would characterise the book entirely. And I felt the more mysterious elements were there not to be resolved so much as to add to that evocative world-building—the books’ sense of mystery feels far more important than the mystery itself. So on the one hand I was disappointed that there was not some greater reward for my pains picking up on all these tiny details, whilst on the other I wish I had left them to be as mysterious as they were intended.

I think my other problem lies with Severian. First of all, he’s a misogynist, and Wolfe has no problem offering him up naked woman after naked woman who are ready to fall at his feet regardless. Yawn. I don’t think we’re offered quite enough moral distancing from Severian through whatever technique Wolfe might have made use of to allow us to better understand this facet of his character (no allusions to the fact that he grew up only around men, or wry dialogue from any of these women that might show us we aren’t seeing the full picture), so I can only conclude it’s to make him seem cool. Had I had no other issues, perhaps I could overlook it, but because I didn’t love other parts of the book, it became increasingly annoying as I went on.

My key problem, though, is the way he narrates. He tells us this story retrospectively, but he is unusual in that he can remember everything that ever happened to him with perfect clarity, so much so that when he recalls it, it is almost as if he relives it. At some points in the book, this also means that he is narrating recalling something in the moment as it was lived. Even more confusingly, he ends up absorbing others’ memories into his psyche, so sometimes they aren’t even his own memories. This could have been an interesting conceit, but it doesn’t quite work. It means whatever retrospective perspective we might have is collapsed, flattening the dynamic. Though he nominally changes for the better over the course of the book, it doesn’t feel very convincing because he delivers everything in much the same tone; he is recalling and living and narrating all at the same time for us, and all from the same pivotal moment at which the book ends. We are not afforded a sense of progression. For such a spiritual novel (more on that in a moment), we never get to a truly epiphanic or revelatory register, which is weird. It makes the book feel… stuck somehow.

On a more specific level, the final volume is a particular disappointment (in fact I think they get incrementally worse as you go along—the first remains my favourite). I really don’t feel like Wolfe had worked out entirely where he wanted Severian to go, and specifically how he was going to wrap up this story, when he sat down to write it. It felt half-hearted, the pacing slackened to an almost dead stop, and there was too much irrelevant material. Also, Wolfe was a devout Catholic, and it’s no secret that these novels are Christian in ethic and viewpoint. This is fascinating to me in a contextual sense—why on earth would Wolfe depict Severian in this rather morally ambiguous way when he is supposed to be a Christ-like figure (or at least just as a Christian figure)? But in terms of the novel as artwork, I think at the end it probably does get in the way of what could have been a more satisfying and successful conclusion to the series, in terms of its plot and outlook.

Overall, I didn’t hate this series by any means, but neither did I love it. It’s a shame because I felt it had real potential to become a personal favourite for the depth of the world itself, but ultimately I don’t think it is fully realised at a character or plot level. I wouldn’t rule out a possible re-read, though, to see if I can glean a bit more of its meaning, so clearly it didn’t entirely alienate me. I’ll also be exploring his other works set in this world, starting with the coda to this series, The Urth of the New Sun.

Peace by Gene Wolfe (1975)

Yep, I read a lot of Gene Wolfe this month! Last year when I was doing a bit of research into his career, this book repeatedly came up as one of his other ‘great’ works alongside the magnum opus above.

It’s hard to know how much to give away about the plot of this novel, and how much should be left to discover yourself. Elderly man Alden Dennis Weer is woken one night by a tree falling outside his house, prompting him to write down what essentially amounts to the story of his life, though told in a rather idiosyncratic manner. We see scenes from his childhood in great detail, but skip over (seemingly very important!) years or even decades. It’s all a bit muddled up—why? Well, you’d have to read it and see.

Again, sometimes Wolfe’s prose sentence-to-sentence requires a bit of careful parsing to figure out exactly what is happening, though the more impenetrable transitions are interpolated with all sorts of rather enjoyable (and very readable) stuff—we have folktales that Weer enjoyed as a boy, at least one horror story, and a whole chapter dedicated to his independent aunt and her many suitors (fun!) Wolfe has a real talent for this sort of folksy storytelling, and I enjoyed his depiction of Weer growing up in the Midwest in the early twentieth century.

There is, however, a certain unfinished quality to many of the stories here, which is no doubt purposeful and suits Wolfe’s intentions with the book, but naturally led to some dissatisfaction on my part. I closed the novel feeling rather disgruntled with it on this basis. Like BONS, it too is figured as a kind of puzzle, but I felt I had more or less got the gist of it and wasn’t altogether impressed with the whole.

But then I wrote up my notes and paged through it again, and realised that perhaps there was more here than meets the eye (even though I read it rather closely anyway!) and that I had also enjoyed quite a few of the sections even if it didn’t necessarily feel like it entirely cohered (I read it over a long-ish period of time, which didn’t help). So I have in fact made plans to re-read it this summer before I forget too much, and see what I make of it after round two.

I’m also keen to read it alongside Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine, as I think they would complement one another very well. Dandelion Wine is also a coming-of-age tale of sorts set in the Midwest in the early twentieth century, and also has a fairly disjointed style (this one because it was originally conceived of as a selection of short stories). It, too, has at least one whole and complete horror story in its pages, and features a strange mix of realism and speculative. But Bradbury’s novel is most definitely the warmer of the two—there is a dark undercurrent to Peace (who is our narrator, really, and what has he done?) that I look forward to pinpointing a bit better next time around. So more on this one to follow, I suppose!

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

Isabella Hammad delivered the first half of this volume as a lecture at Columbia University nine days before October 7th, and it is published here with the addition of a searing afterword written in January 2024 in the light of Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza that is yet ongoing. (At the time of my writing this, no aid or food has entered Gaza since March due to an imposed blockade, resulting in widespread famine. It is absolutely unthinkable—some basic things we can all do today here.)

As soon as I first heard Hammad mention this book (in an interview from last year’s Hay Festival), I knew I had to read it as soon as I could. Narrative and narrativization—and how these things interact with the real world—are particular interests of mine, and I was already impressed with her approach to them in her latest novel, Enter Ghost. As expected, her ideas about narrative and the problem of narrative for Palestinians were astutely argued and illuminating in many ways; for the wider world, for Palestine, for literature, and for her own work. She’s undoubtedly an author whose output I’ll continue to follow closely.

The second half provides us with the harrowing details of the first three months of Israel’s action in Gaza. There will be nothing new here for anyone who has followed it closely, but the juxtaposition of the two parts made for particularly heartbreaking reading. A book I recommend to all.

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton (2024)

This is a very enjoyable nature memoir about a woman who ended up raising a hare during the early stages of COVID. Before the world shut down, Dalton lived a fast-paced lifestyle as a political adviser, and never settled anywhere for long, thriving on the adrenaline rush of her job. When she finds an abandoned leveret in the middle of a path near her house in the country, she feels unable to leave it there and let nature run its course despite her fears about interfering with a wild animal. The first part of the book is certainly the best part; there is some real tension in those shaky early days as she tries to maintain the hare’s wildness but also keep it alive.

Living in tandem with the hare, she explains, helped her see what her life was missing, and the joys of rootedness and time in nature. That’s the premise of the memoir, but it is lightly referred to within its pages. This book is not really about Dalton, it’s about the hare. And she writes the hare beautifully. Whilst very occasionally some of the hare facts—a must for a nature memoir like this one—felt shoehorned in, in general Dalton is a very accomplished, readable writer.

You shouldn’t expect reams of introspection or a more in-depth or nuanced take on the issues within. Suggestions for how we might live differently as a society are briefly offered. Very often this would irritate me in a book—I’d want more rigour—but it didn’t here. I could see that Dalton wanted to memorialise this time with the hare in some way, and she chose to do it in book form. It felt like an ode to that unique and beautiful experience, without her having to sacrifice too much of her privacy, and good for her (memoirs are tricky things for me on this front). It is a light read, but I still felt the tread of little hare paw prints on my heart by the end. I felt sad to say goodbye to the hare by the end of the book, enough to bring a tear to my eye during Dalton’s poignant final message. Whilst I wouldn’t say you need to rush out and read this, I can’t help but feel very fond of it. So perhaps you should at least amble out to read it, fairly soon.

Out of the Past: Tales of Haunting History ed. by Aaron Worth

I am currently subscribed to the British Library’s Tales of the Weird offering. I pay them a monthly fee, they send out a weird title of some kind—often a collection of stories, but occasionally a reprinted novel. Some of these are great, and inevitably some of them are pretty disappointing. This series has been going on for quite some time now, and I am beginning to wonder if the British Library is running out of good stuff to reprint from their archives. Especially in a genre like this one—encompassing supernatural stories, the gothic, and early science fiction—which can turn the bad kind of pulpy at the drop of a hat. Or perhaps I’m just a bit jaded because the most recent one I read was this one, and it was not their finest.

There was potential—it’s a collection of weird historical stories. I’m on a historical fiction kick at the moment so this should have been right up my street. Alas. They were mostly pretty dull which is perhaps the worst thing you can say about a collection of this kind? I won’t deny that I did skip one or two. It definitely warms up a bit as we get toward the end and the newer stories, particularly the editor’s own that he snuck in there. I don’t know whether to blame him for picking the other stories or thank him for saving it with his own. Honestly I should have given up with these but thought I should at least give each individual story a go, and it took me months. I will try another volume though soon, though, as they are beginning to pile up.

Reading projects - sagas, poetry, graphic novels

I thought I would group the below as these are my current reading projects. In theory I’m supposed to be reading one saga, one poetry collection, and one graphic novel a month, though results are variable. Regardless of my ability to keep up, though, I am enjoying exploring literature outside my usual novels.

Egil’s Saga by Unknown (1240)

Following on from my success with contemporary novels written in the style of Icelandic sagas earlier this year—The Long Ships and The Greenlanders—I decided to go back and read the originals! There is something about this style that I’m drawn to. It’s been a welcome break from contemporary literature and prose styling, and can achieve a remarkable degree of nuance and subtlety using totally different methods to literary realism.

The Icelandic sagas are medieval literatures hailing from Scandinavia that—unusually for the time—are written in prose. They are also unusual in that they mostly describe the lives of fairly ordinary people—farmers, warriors and the like. There is something utterly compelling about them, especially compared to my experiences with other medieval literatures (though I don’t rule out returning to those at some point outside the bounds of an educational facility!) They are at once completely recognisable—these are characters that are motivated by the same spectrum of human inclinations as ourselves: jealousy, greed, love, dignity, pride. And the form itself does call to mind the modern novel, not only because they are in prose but also because of the nature of their content—relatively ordinary people living ordinary lives. Yet they are also utterly alien in other ways, denoting valuable information about this strange Viking world where it’s perfectly normal to spend the summers looting neighbouring countries for ‘booty’.

Anyway, I started with Egil’s Saga, thought to be one of the best of the collection of sagas that has survived with us until today. I’m reading from the Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition which is a nice collection of quite a few of them, though of course you can read each volume individually, too.

I thoroughly enjoyed this! Egil and his family have a feud going on with the kings of Norway, and must flee to newly-settled Iceland to escape punishment. The saga follows Egil as he travels back and forth between the countries, variously escaping the wrath or courting the approval of different kings across Northern Europe, getting into scrapes and antagonising yet more folk, and on occasion peacefully farming his land. Egil is a skilled poet but a pretty brutal man, and there are some eye-poppingly violent scenes here, described with an almost cinematic effect. It was an engaging and rollicking read, elevated by the periodic shift into ambiguous moral territory when we have to ask ourselves if we admire this hot-headed man for living by his own code, even if it seems otherwise untenable? Double-edged dialogue seems to provide the literary complexity of these sagas, but also confounds understanding of their underlying truths at the same time.

I think I’ll be better able to evaluate these and my experience with them once I’ve read a few more, so stay tuned on that front. Next up is the The Saga of the People of Laxárdal.

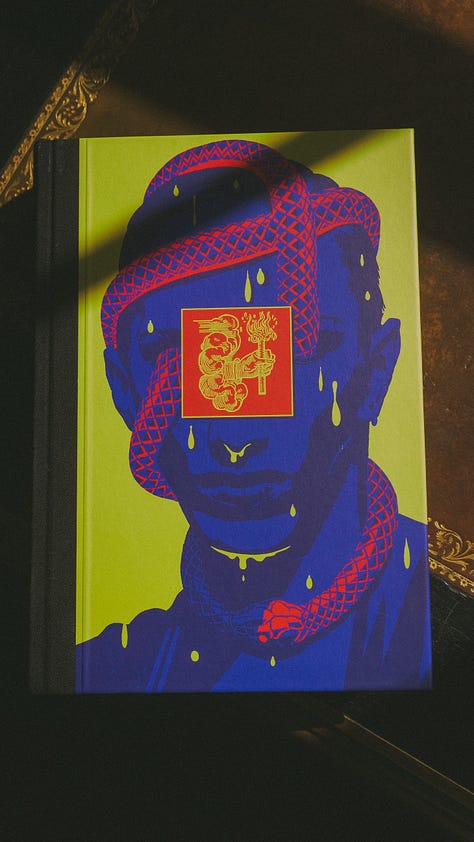

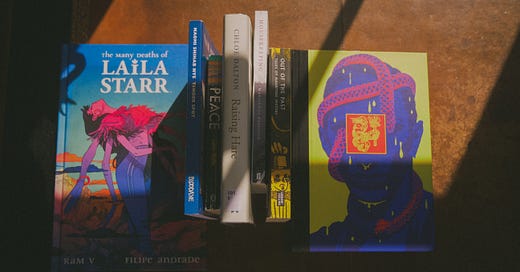

The Many Deaths of Laila Starr by Ram V, illustrated by Filipe Andrade (2022)

I spent a couple very bunged-up fluey hours with this graphic novel, and enjoyed my time with it. I’m trying to read more graphic novels this year—apparently in the hopes that I can add yet more reading material into my life?

No, but really, I’m interested in the art form, the interactions between illustration and the text, and what this medium might be able to do that others can’t. I spend a lot of my time reading picture books to my daughter, and I’ve been impressed (and become slightly obsessed) with how powerful the marriage of the two things can be, and how much artistry it takes to nail it—whether that’s across one or two people. So it only makes sense to look at the more expanded, complex version of something like that. I daren’t say grown-up version because I’ll soon be making the case that picture books are for everyone (and are a singular art form, just as the graphic novel is).

Knowing as little as I do, I’ve been letting myself be led by the occasional recommendation (this one came from book club—thank you Pran!) I do think moving forward I’m going to go for the big hitters—Persepolis, Fun Home—and work outwards from there as my knowledge grows. As always, I’m looking for stuff that has literary merit, and naturally conforms to my taste in novels and literature in general. This is the stuff that I think is probably harder to find, hence my mission to find it and tell you about it.

Anyway, back to Laila Starr. Death has just been fired. Apparently, a child has been born who will invent an elixir for immortality, making her obsolete. As recompense, she is sent down to Earth for the first time in a human body (something she’s not altogether happy about at first). Over the course of several issues (collected in one volume as I read it), newly-named Laila comes into contact with the boy who changed the trajectory of her life, and discovers what it means to love and to lose. I admit, it did make me tear up by the end. You can tell that the collaboration between Ram V and Filipe Andrade was a productive one, and the story is well-supported by the latter’s illustrations with beautiful colouring from Inês Amaro—it is beautiful to look at, and the rhythm of the panels adds to the poignancy of the tale.

The story itself is nothing very groundbreaking, and I can’t say that I’ve thought about it a lot since I finished it. I think I’m probably more of a fan of Andrade’s vivid and lively illustrations than I am of the writing itself. That’s not to say it was bad, but not particularly memorable (especially as a novel-reader by nature). As I said, though, I had a nice time with it for a couple of hours.

Tender Spot by Naomi Shihab Nye

This volume encompasses some of Palestinian-American poet Naomi Shihab Nye’s best work from a number of her poetry collections over the years. With such an expansive view of her career, I felt like I was dipping a toe into different periods of her life and perhaps missed the greater focus of Imtiaz Dharker’s singular Over the Moon—a helpful thing for me to know about my poetry preferences, especially with contemporary work. A collection conceived as a whole may work better for me than a compendium of sorts. (Over the Moon was the last collection I read; I am trying to read a collection of poetry a month—more or less!—and am dutifully documenting it here, but I do have far less expertise in poetry and am recommending mostly on vibes.)

That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy many of these poems! I marked down lots of favourites, and have chosen a few of them to highlight for you. Nye has a beautiful way of using everyday language with a clarity that reveals the edges and seams of life, and that is able to surprise in imagery and tone. Her poems are easy to read, and yet still have the effect of making you stop for a moment to contemplate what she’s just said. Some of my favourites were a little long, so I’ve linked them rather than transcribed them. Many of her poems covering Palestine, and her father or grandmother’s relationship to Palestine, were particularly beautiful to read.

‘The Only Democracy in the Middle East’

Books from How to Read and Analyse a Novel:

I won’t expand too much more on these books, partly because I’ve already reviewed them, and partly because I wrote many, many words about them in April through the course itself. I’m tired!!! All you really need to know is—these are excellent books! And if you want more info, you’ll just have to join us on the course, won’t you ;)

Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad - original review - course post

As wonderful as I remember it last year. This is fantastic literary fiction that I implore you to read.

Telephone by Percival Everett - original review - course post

Everett at his most elegiac, but without giving up the formal play that makes him such an interesting novelist.

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson - original review - course post

Small but perfectly formed novella about a lost way of life.

The Doloriad by Missouri Williams - original review - course post

A remarkable debut about human life after the apocalypse. Williams is one to watch!

That’s it! Congratulations if you made it this far.

In my next monthly round-up, I’ll be reviewing The Last of Her Kind by Sigrid Nunez, The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell and This is Happiness by Niall Williams (amongst other things!)

I'm always looking for graphic novel recommendations and I didn't know the one you mentioned so thank you for that! One I can recommend in return is "Shubeik Lubeik" about an alternate reality where there are dreams available to buy. It was written and illustrated by an Egyptian writer Deena Mohamed. I thought the world she created was fascinating and deeply rooted in the real one that we live in, with all its flaws (i.e. colonialism and capitalism). I've also heard good things about "Feeding Ghosts", a graphic memoir that was just awarded the Pulitzer prize.

What a fascinating reading roundup because I have hardly heard of any of these (except Recognising the Stranger which I still need to read!) I might however opt for The Parisian first from her. I am also very intrigued by the soft love you seem to have for Raising Hare - my childhood teddy was (is - he remains with me) a hare! And so hare's have become something I always get on cards, pjs, often anything my mum buys me, so I can foresee some affection and tears from me too towards that book!