February 2025 Reads

Nicola Griffith, Rachel Cusk, Jane Smiley, Rollan Seisenbayev, Imtiaz Dharker, Francis Spufford

This post is too long for email, so please do click through to the app or your browser to read the whole thing.

Welcome to one of my monthly wrap-up posts, where I briefly review everything I read! I read widely across many genres, from classics to literary to speculative fiction. With these I’m hoping to shed some light on backlist gems, perhaps push you to read outside your genre comfort zone, and also highlight which new releases are worth your time.

This month was dominated by long, dense reads that were nonetheless very enjoyable. Plus finally reading some Rachel Cusk, which I’ve been meaning to do for a long time.

Some links to books below are affiliate links.

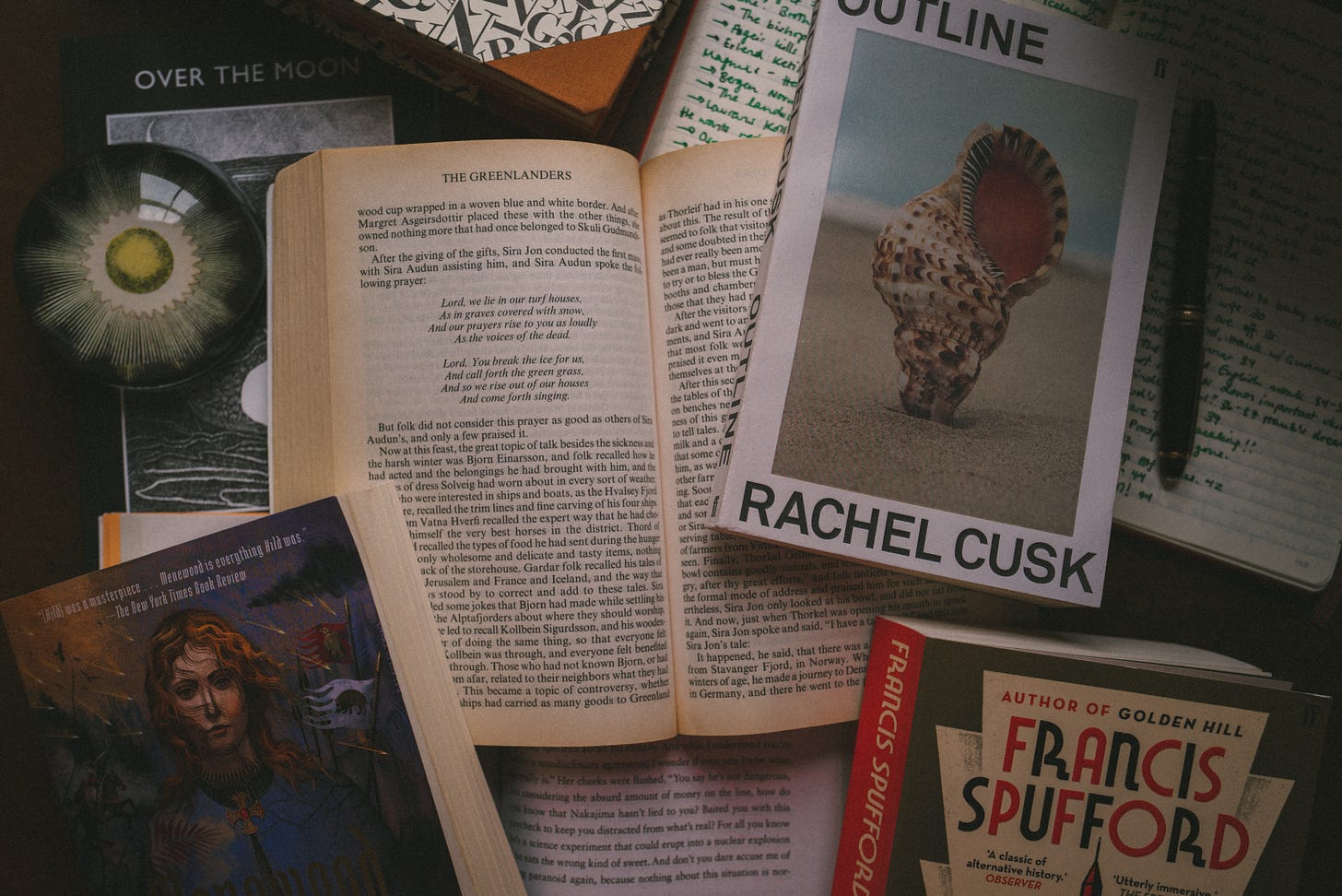

Menewood by Nicola Griffith (2023)

There’s something about Hild. Saint Hilda, you may know her as, or Hilda of Whitby. She lived in 7th Century Britain, and wielded a fair amount of power and influence (insert “for a woman at the time”), founding a monastery and dispensing advice to kings—enough for Bede to include a few paragraphs on her in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Griffith, intrigued by her story, has now written two novels speculating on what kind of early life she might have led to get her into this position of power; Hild covering her childhood, and Menewood her late teens and early adulthood.

And like I said, there’s something about her, or at least the way Griffith writes her. We spend so much time right up next to her, seeing the landscape the way she does, feeling her shift and breathe, and try to navigate a world fraught with dangers and difficulties. Reading these books—if you can find their rhythm—is an incredibly immersive experience. It is something few authors can achieve and speaks to Griffith’s eye for detail and absolute commitment to fully imagining and recreating the alien world that was this isle 1,400 years ago.

But like I say, this is only if you find their rhythm. I don’t think these books will appeal to everyone, and if they did they’d probably lose their magic. These are densely written novels, filled with minutiae, tons of difficult names (the Osfriths, Osrics, Oswines did rattle my brain this time round) and a lot of different kings and kingdoms to keep track of.1 Menewood is slightly more straightforward at a sentence level and has much more forward motion as a result, but I did mourn slightly the poetics of Hild. I think Hild is probably the towering achievement here.

Although I did have niggles about Menewood when I switched on my analytical brain—there’s some unnecessary repetition; I wasn’t sure about all the plotting choices; it feels like it could be tauter, tighter, cleaner—ultimately I forgive almost everything because reading this book has me genuinely gripped. I really care. It wielded a real power over me. And there’s a limit to how much I can criticise Griffith when some things feel like a divergence of taste between us—she wants Hild to become a warrior in Menewood, and I probably would have preferred a different arc—but that’s hardly a fault in the book itself.2 Ultimately I was willing to trust what she did with it and her interpretation.

I think you would be hard pushed to come away from these books without feeling a certain sense of awe at what Griffith does here. The way she holds the vast historical dynamics of the time and the small details of everyday survival together is nothing short of incredible. Add to that her depiction of Hild: I cried when Hild cried, my heart raced when hers raced. To enter this world you do have to give a little of yourself, a little of your time and effort and patience—but my, is it worth it. I’m just hoping we don’t have to wait another ten years for the next.

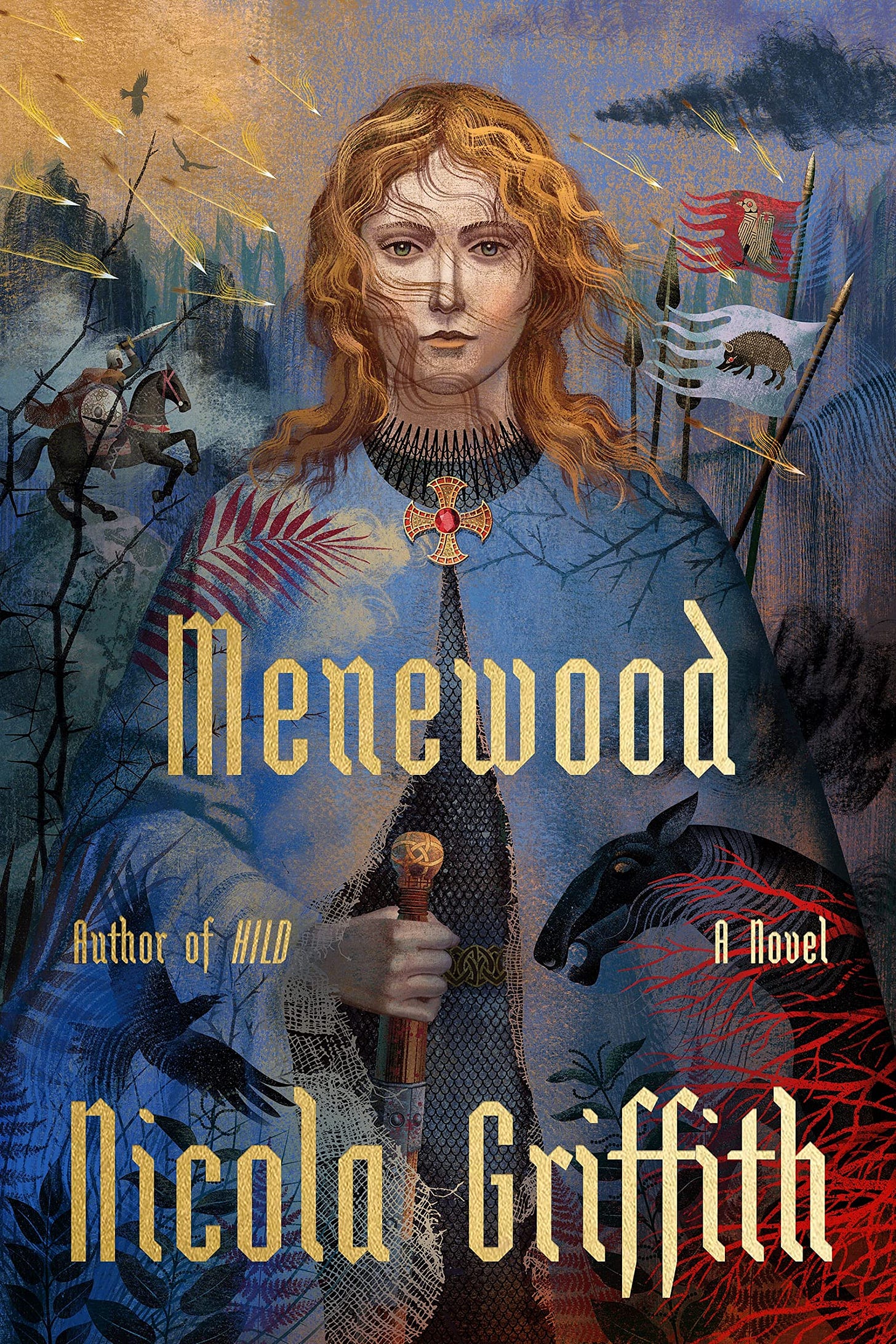

The Greenlanders by Jane Smiley (1988)

I’ve been singing this book’s praises for many years and thankfully for me, it is actually very good. I’ve wanted to re-read it since the moment I finished it the first time in 2019, and have dutifully carried it with me to a number of places where it always somehow slipped down the list. Unfortunately for me, I want to re-read it again already.

There are many technical things that I think make this book a minor masterpiece, but that still wouldn’t quite explain why I am so drawn to it. It certainly doesn’t have the same effect on everyone. But still, let me make an attempt.

Smiley writes in the style of an Icelandic saga here, telling the story of ‘the Greenlanders’, Norse peoples who had settled on the shores of Greenland from the tenth century. For a few hundred years they lived fairly prosperously there until around the fourteenth century, when the book picks up; soon after, the settlements were entirely abandoned. Though there are plenty of theories, we don’t know exactly why this happened—Smiley posits a selection of her own in the novel which feel entirely plausible.

Having just read Swedish author Frans G. Bengtsson’s take on an Icelandic saga in The Long Ships, I was keen to see how this novel differed, and what gave it its tone and feel. Bengtsson’s book is generally much wittier, lighter, fleeter of foot. Smiley’s novel is much darker, much denser. Whilst the first time around I was mostly just taken with the archaic writing style, this time I could see the influence of American literature in her work. It’s subtle, but it’s there. Her themes and the way she elucidates them through a series of symbolic images or refrains felt like the markers of an author who has read some Hemingway, some Steinbeck. So, too, is the mark of the 80s on this book. Whilst it starts out more formalised and saga-like, as we get deeper into these characters’ lives, we are caught in their entangled webs of human folly. We are afforded a closer attendance to a small subset of characters; we are privy to their thoughts and there are more extended dialogue scenes. I would assume these things mark the book as different from the original sagas, though I could be wrong. Either way, I’ll be able to tell you soon as I ordered myself a fat volume of them to work my way through. I’m very much in saga-mode at the moment.

This combination of the archaic, slightly removed style with the heft of emotion and careful human observation from contemporary writing is magic to me. She brings some of what is best about old modes of storytelling—assured manipulation of time, restraint and balance, lots of plot—with some of the best of what is new—sophisticated thematic choices that bring deeper meaning to the whole.

In short we follow a pair of siblings, Margret Asgeirdottir and Gunnar Asgeirsson, and their attempts to carve out a living for themselves in this unyielding place, and in the face of many tragedies. But the narrative is wide-ranging, and we encounter a lot of other characters and stories along the way. It’s another one of those books where you have a lot of names thrown at you. There’s a list (and some maps) to help you, but writing a few notes of your own might be helpful. As I say, though, the book’s focus does narrow down as you go on.

I must leave you with my usual Greenlanders warnings. The style of it will get in the way of some readers’ enjoyment. Compared to Bengtsson—which is much more accessible—Smiley’s prose feels more rigid and formalised, at least at first. I also spent the first seventy pages or so wondering whether the book was going to live up to my expectations. It is very much a slow burner in the way it works on you. It wasn’t until probably about halfway through that I remembered why I loved it quite so much. It takes time to get to know the characters (but the arcs! Oh the character arcs!) The first time round it took me a few weeks of reflecting on it to fully appreciate it, so this is an improvement. To me, it is entirely worth the trouble. A small miracle of a book.

The Vanished Birds by Simon Jimenez (2020)

I spent much of my time in the last few months of 2024 raving about Simon Jimenez’ The Spear Cuts Through Water, so I was very pleased to read this, his debut novel, with book club this month.

Whilst Spear is epic fantasy, here Jimenez tackles science fiction with a space opera style setting. We follow a small cast of characters that revolve around a mysterious silent boy who careens out of the sky one day. He forms an attachment with an aloof spaceship captain, and the two must cross worlds to keep him safe, as he has a power that is particularly sought after by the powers that be.

This little two-sentence summary doesn’t really do justice to how it feels to read this book. It was conceived of during Jimenez’ MFA programme, and so it starts off almost as a selection of lightly interconnected short stories before it begins to cohere together. In general it really has the feel of a debut novel; Jimenez tries all sorts of different techniques and voices out in it, in ways that are variously successful. I felt quite kindly toward it on this basis, you could see some of his talent beginning to come through, even if this wasn’t quite the right story or collection of characters. He is at his best when he writes a more focussed, concrete setting, where his imagery can really sing—the scope of the universe was just too big for him here.

But overall I actually really enjoyed my reading experience, even as I noted the parts of the book that just didn’t work. I am soppy and sentimental at heart, and this novel hit the right beats for me. I was able to fill in the gaps myself where needed. Nonetheless, I don’t know that I’d outright recommend it unless you loved Spear and want to see flashes of that same brilliance in his debut.

Outline by Rachel Cusk (2014)

There are a few things to check at the door when starting Rachel Cusk’s Outline, but the most important one is your sense of it as a work of realism. I am very aware of the artificialities of literary realism of all kinds, but this novel struck me as going far beyond them, into much stranger waters.

The thing is, is that realism—or at least the very internalised “new realism” of the likes of Ottessa Moshfegh or Jenny Offill—was what I was expecting, and so I was left pretty confused by this book. I then wrote close to two thousand words about it and now have to acknowledge that perhaps I need a little perspective shift. If a novel gets me thinking that much about how narrative is done, then it has achieved something. I certainly couldn’t write anywhere near that amount about, say, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which I found to be a rather empty endeavour.3

It is, famously, a novel in ten conversations (or at least ten chapters). Through these conversations, we are offered insight into the various characters depicted and their internal lives, as well as given an outline of sorts of our protagonist, the person whose perspective we actually inhabit. This character, Faye, is a writer, and she has agreed to teach writing to some students in Athens for a week or so. I was nervous that this would be wholly plotless, as it is often said to be, but actually there was enough concrete detail in each of the monologists stories that there is more than enough to go on, narrative-wise.

Analysing it as a piece of realism is a frustrating experience. I lost count of how many times I wrote in the margins ‘nobody talks like this’.4 The style is artfully poised, somewhat removed. All the characters across all the conversations sound much the same. It is, at times, verging on the ridiculous, in the way it describes absolutely everything that Faye observes through the lens of some grander philosophical narrative (a stranger’s hairy back “a foreign country I was lost in”, the opening or shutting of windows a lesson in “inversions of reality”). There is very little tonal shifting throughout, everything touches on the existential in a way that can feel forced. This is not a novel of light and shade, but an increasingly urgent monotone. Toward the end we meet a playwright who describes an affliction she calls “summing up”, whereby she keeps whittling all her ideas down to one word until she can no longer work on them. It culminates in this sentence: “And not just books either, it was starting to happen with people — she was having a drink with a friend the other night and she looked across the table and thought, friend, with the result that she strongly suspected their friendship was over.” Needless to say, if you thought Cusk was aiming for realism here, you might think rather poorly of the whole endeavour.

You might be forgiven for assuming it was so, though, because of the minute physical details and acts of ‘noticing’ that Faye feeds us, stuff that feels incongruous to the nigh-on Socratic dialogue that is the rest of the book. I say noticing because when she teaches her writing students about writing, a lot of it seems to be about noticing. Of course, I am very much of the mindset that noticing and writing down what you notice does not amount to good storytelling. But the contrast between these highly personal stories shared at the drop of a hat (complete with full philosophical and moral implications rendered in abstracted and impersonal language) and what we can assume passes for realism for Cusk—the small physical details of the way someone’s lips move when they talk, or the tracking of their eyes—this discordance is where my fascination truly lies with this book. To me it becomes almost uncanny in its unhumanness, and this in turn creates an interesting effect. And as a novel, for me, it’s all very odd. And yet I can’t deny that what Cusk produces is actually a pretty interesting version of a novel, even if it’s not my preferred type. What is she trying to achieve here, and why?5

Hannah Tennant-Moore talked in her review about an undercurrent of rage in this novel that she wishes Cusk had tapped into. It is obvious that the main theme across all the stories is the fraught nature of the relationships between men and women.6 One of the few details we know about Faye is that her marriage and family life as she knew it is falling apart. Cusk herself has written repeatedly of her own divorce, and so some sort of collapsing of Faye and Cusk is inevitable.7 On the one hand, I am tempted to say this novel is a failure in terms of how it depicts Faye. We get very little sense of her at all, despite the concept of the novel as a whole. And yet on the other I realise that perhaps the overall tone, the absurdity of the novel—perhaps that does feed into how I think of Faye (and, due to inevitable collapsing, Cusk). Perhaps I am shown a way of seeing the world that is, in many ways, alien to my own, and that is, in fact, quite revealing.8

It’s hard to tell where Cusk and I meet. Am I affording her too much grace for a novel which is—to my mind—at points ridiculous, strained?9 Devoid of actual life? Or is it in fact entirely her intention for it to feel this way? Does she intend to reveal herself, or is it Faye? How similar are they—where does the writing style of Cusk slip into the characterisation of Faye? What does it say about our narrator’s relationship to the concept of story as a whole? Is it as simple as that she is obscure to us because she is so obscure to herself? Is what I’m interested in in the book how far it reveals Rachel Cusk herself, writing fiction even though she doesn’t read fiction anymore? Or the modern subject? Or what it reveals about how we conceive of fiction in our current climate, what we (not me) value, why we value it?

Whatever the case may be, it has got me thinking, so it has in some ways been a success. I don’t particularly like it—I like my novels to have more humanity in them—but why should I like it? Certainly it deserves to exist. Many novelists have attempted to play with and resist the novel form and have ended up with something that is actually just very dull. This I think is doing… something. I think I’ll be continuing with the trilogy to see what that something might be.

The Dead Wander in the Desert by Rollan Seisenbayev, translated by John Farndon and Olga Nakston (original 1991, translation 2019)

This book documents the death of the Aral Sea at the hands of the Soviet Union and their grand agricultural plans. For those that don’t know, the Aral Sea was one of the largest lakes in the world, spanning multiple Central Asian countries. Today only 10% of it remains, leaving behind what is now mostly desert. Ironically, it is because the Soviet Union wanted to ‘irrigate the desert’ to grow crops like cotton and rice that the two main rivers that fed into the Aral Sea were diverted, inefficiently and without thought to the unthinkable damage to the ecosystem. Seisenbayev—a prominent figure in Kazakhstan’s movement to independence—writes here a suitably apocalyptic novel, for a truly apocalyptic event.

Although the cast of characters might seem large, the narrative really focuses on Nasyr—a fisherman and mullah in a small village on the receding coastline of the Sea—and his son, Kakharman. Whilst Nasyr refuses to leave Sinemorye, as so many of his neighbours and friends do, Kakharman tries to fight the overwhelming deafness of Soviet bureaucracy from within, teaming up with scientists—Russian and Kazakh—to try and make them see sense. I don’t need to tell you that he fails in this, and the despair they all feel at witnessing this ecological disaster is palpable throughout. A note to say at times this book gets very dark—the people were pushed to the absolute brink.

As I often do when I encounter a book from an entirely new culture, I feel pretty out of my depth reviewing or evaluating this book. I think I’d have to read a few more books from Kazakh authors to understand which parts of the book comprise artistic choices, and which are inevitable as a result of Seisenbayev’s own literary and cultural experience. In general it has quite a grand, sweeping style to it that I would suspect has an even greater lyricism in the Russian in which it was originally written (I don’t tend to find this style works as well in English). We spend time on the small things, like following Kakharman into Party meetings, or sitting with Nasyr and his wife in the increasingly empty village, but there are also scenes of enormous impact and drama. I’m thinking of one in particular in which a helicopter is caught in a deadly tornado, and a fiery stallion flying through the air is the last thing the scientists inside it see. Not to mention the true magical realism elements (if that’s even the right term for the specific narrative style Seisenbayev employs here), where an enormous catfish might choose to talk to you, or the dead speak from beyond the grave.

I can’t say that Seisenbayev’s is a style I am particularly drawn to in general—I love precision in all things narrative, and folk epic is not generally my preferred genre—but that’s certainly more of a preference than a criticism of the book or Seisenbayev’s project with it. It certainly gave me a starting point and a glimpse into the culture and the history of the Kazakh people, and I will be seeking out more (I have my eye on Amanai and Zamanai by Saken Zhunuzov next, but do let me know if you know of others—there are not many translated works out there to get hold of). And I do recommend it to anyone looking for a book from this part of the world.

Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford (2023)

Around a thousand years ago, Cahokia was a large and prosperous pre-American city with a population similar to that of London’s at the time. It was eventually abandoned in somewhat mysterious circumstances. In this alternate history novel, British author Francis Spufford imagines that this city continued to grow and develop under the guiding hand of its Native American inhabitants until at least 1920, when this book is set. In his version of our world, smallpox didn’t have such a devastating effect on the Native American population, such that more significant pockets of America were able to remain under their control, including the state (and city) of Cahokia.10 Unsurprisingly, this doesn’t sit right with the white settlers and states that surround it, leading to some of the major tensions of the book.

I’m not entirely sure what to make of this novel. On the one hand, it was a very solid take on 1920s noir fiction, making it a rollicking read with bags of plot and atmosphere, and the alternate history element added some extra speculative interest. Some of it was a bit laughable (particularly the love story), but I think that’s part and parcel of the genre Spufford is working in. We follow Joe Barrow and his partner Phin Drummond who are called to investigate a strange murder one night: a body has been found pinned to the top of a skyscraper with its heart ripped out. As the two try to track down the murderer, tensions in the city begin to rise. Not only that, but Joe Barrow himself is experiencing a sort of awakening, leading him to re-examine the life he has built.

In many ways it is clear that Spufford is a talented novelist. It does what it needs to do, which is: entertain! And I’m keen to allow scope for authors to explore life outside the boundaries of their own experience; it just makes for better art. Ultimately I tentatively conclude that he does the best he can with transposing Native American city culture into the 1920s noir setting, coming up with some interesting ways that it might have had to adapt to fit this particular story. Whilst it isn’t glaring when you read the book, as I reflected more and went back over my notes, I do think he has several blind spots that would be better addressed by someone more familiar with the material, and he probably made some choices I would have avoided. I would love to read a Native American author’s response to this book in novel form, I would love to read more alternate history of this kind!11 I think a book like this poses a question to the world, and the reading experience would be made richer by having that response. If you already know of a book doing just that, please do let me know.

Over the Moon by Imtiaz Dharker (2014)

It’s my aim to read a book of poetry each month this year, although I admit this was left over from January. I picked this collection up because I read and loved a poem called ‘This Room’ in the Being Alive anthology, and then saw that Tasnim had highlighted this particular volume of hers in her 31 days of poetry last year, so when it came time to look for something, I thought I would start here. Excuse my sharing quite a few of her poems with you today, but I think one of the best ways to review poetry is actually just to share some examples for you. Here is the original poem that I loved:

This Room

This room is breaking out of itself, cracking through its own walls in search of space, light, empty air. The bed is lifting out of its nightmares. From dark corners, chairs are rising up to crash through clouds. This is the time and place to be alive: when the daily furniture of our lives stirs, when the improbable arrives. Pots and pans bang together in celebration, clang past the crowd of garlic, onions, spices, fly by the ceiling fan. No one is looking for the door. In all this excitement I'm wondering where I've left my feet, and why my hands are outside, clapping.

One thing I love about what I’ve read about Dharker’s work so far, including the poem that Tasnim shared in her post, is her ability to highlight beauty in the ordinary moments. The sense of joy that rises off This Room is almost tangible. There is also a playfulness to some of her work that provides balance to some of the darker themes, and gives them a really distinct voice.

Over the Moon starts largely by documenting Dharker’s life in London (though there are still interludes from other places she calls home), and I so enjoyed seeing my city through her eyes.

The City

Hauls itself out of riversilt and swamp, trailing marshdamp and the warmth of creatures it has slept with all these years. Makes itself up in layers, from clay and chalk, brick by brick of London stock, standing not on solid rock, but breathing water. Rises up at Ludgate Hill to feel the people flowing through it veins, and still, the secrets in its underdank, its lates, Ropemaker Street, Saddler's Hill, Goldsmith Street, Ironmonger Lane, a geography of daily needs. The City maps its appetites, its hunger, so that even now a woman lifts her mouth in Bread Street, Corn Hill, Milk Street, Honey Lane, to taste the names, and taste the names again. On Wood Street, a thrush begins to sing. Then her eyes remember The colours flood back in.

Part way through writing the collection, though, her husband Simon Powell died after a long illness. Whilst the poems are devastating—and some more despairing than others—they are also filled with her love, and so are absolutely beautiful to read:

Vigil

Your eyes open, silver for one second, close. Your hand stops, falls still. You send me no more messages. The machine by your bed is saying prayers for you. It keeps watch, tenderly interpreting your body's needs. It listens and records your every breath, the turning of your blood, your heartbeat. All night, all night, it pays close attention to you. At dawn it stops. I try to read its face. The machine is blinking back its tears.

Vroom

This month is the arsonist. It strikes its match and trees catch fire down every street, out across the country lanes, all the way to Wales. No mists here, but the leaves cut out of glass stained crimson, carmine, orange, gold. Your colours fly from every mast. You never belonged down in the tube-lit room, trapped in a web of wires and tubes, and will not stay a minute longer than you must. The machines open their hands, lose their grip on you, and you are gone, flown ahead of us, along the clanging corridor up the stairs and out. Out at last to where the day fires up and speaks to you in tongues of blackbirds, London buses, ars taxis, human voices, trumpets, cymbals, joyful brass. You head off on Brompton Road and the leaves are flames that light you up, your face aglow, not looking back, knowing this is the way to go.

Overall, I highly recommend them. I had to stop myself buying another collection of hers to read for February, thinking I should give another poet a chance…

Here’s what you may have missed since the last monthly wrap-up! If you have adjusted your email notifications, you may not have seen these posts (just so that you don’t miss anything that you do happen to be interested in).

The Minutiae: Completing a Body of Work, Part II

The second part of my completist list! Had a lot of fun putting this together.

How to Read and Analyse a Novel: Reading List

How to Read and Analyse a Novel has officially begun! Start here and get a sense of what the course will provide and what books we'll be reading together in this post. There's still time to catch up, we've been covering the basics so far.

Book Club

In book club this month, we are reading Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson, and Peace by Gene Wolfe. Click here to find out more about what we have going on over there, or here for more details on this month’s picks.

Thanks for reading, everyone! In the next monthly round-up, I’ll be reviewing Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace (yes, really), The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich and The Garden by Nick Newman. Make sure you are subscribed to stay updated, and share with bookish friends if you enjoyed!

The front matter of Menewood contains three maps, a full-spread family tree, and a cast of characters that takes up eight pages. In the back we have Griffith’s note on the historicity of the work, as well as the names and pronunciation notes of various words in the four languages that are used throughout (Old Irish, Ancient British, Latin and Old English). Oh and then there’s a three page glossary (which I wish had been longer).

This would explain why I think I ultimately favour Hild, though. I also have a history of preferring the childhood sections of novels and series, too.

Moshfegh and Cusk are very different authors in many ways, and yet they are often grouped when it comes to people’s literary tastes (if you like one you’ll probably like the other). I think I know why, but I’ll leave that for another time.

A personal favourite: ‘In other words,” Georgeou said, “I could deduce your story from the facts alone, and from my own experience of life, which is all that I know for a certainty, most importantly in this case my experience of failure, such as my failure to memorise the constellations of the southern hemisphere, which never ceases to upset me.” He folded his hands and looked at them with a downcast expression.’ No mention of constellations before this.

I’ve gone down a rabbit hole here but I find it so interesting how she repudiates fiction in general and doesn’t read much of it. Why, then, choose this form? It’s truly fascinating to me, and shows in the writing. What is she trying to push away from herself, and yet is nonetheless still drawn to?

It’s funny because I ‘agree’ with probably about fifty percent of the philosophical takes in the book. They should be ripe for analysing but they’re not, to me, at all. There are too many of them, they’re too scattered and they don’t seem to add up to any cohesive whole beyond ‘men and women will always create an unequal partnership’. In a good book, a book I like, the abstract mode generally really seems to touch something of actual life. Here I think it sometimes does but equally often doesn’t. Like Cusk is sort of stabbing in the dark for meaning.

She has also said she is “certain autobiography is increasingly the only form in all the arts.” I… do not agree lol.

Cusk is sometimes pulled up for not liking people or humanity that much. I would tend to agree.

The fact that she equally described “the idea of making up John and Jane and having them do things together seems utterly ridiculous” means that Cusk and I are at a ridiculosity impasse, which I enjoy.

Taking land from Illinois, Tennessee, Missouri, Mississippi, Arkansas and Kentucky.

Under no illusions that this might already have happened but that Native American authors may have a much harder time getting published than someone like Spufford for many different reasons.

Loved reading your thoughts on Cusk! I remember picking it up years ago from the library just to give it a go and putting it aside because I didn't feel it was my kind of thing. I still think I probably won't pick it up in the future (so many other things I'd rather be reading instead!), but I look forward to reading more of your thoughts on what she seems to be trying to do with the trilogy or her larger body of work. Even though you didn't enjoy it, it does sound like it has given you lots to think about, which is not always the case with these kinds of books. Years down the line you might end up finding that Cusk has actually become foundational for you in finding out/reaffirming some of your opinions on fiction and the novel in general haha

Also, great reminder that I need to pick up Hild and The Greenlanders, which are patiently waiting to be read on my shelves!

I found your Outline review utterly fascinating to read as someone who read the book last summer and just loved it. The 'nobody talks like this' notes in the margins are hilariously real - I think I said in my review something along the lines of everyone in this book is unnaturally thoughtful, philosophical and ridiculous. I think the comment about the undercurrent of rage is really fascinating and since reading your review is such a heavy theme I feel I initially missed. While I loved it, everything you have said makes me laugh because it is true. I think the novel reveals more about Cusk than Faye, and I think the two are almost one. It is interesting you say your like your novels to have more humanity in them, because I thought outline was unfailing human in its exploration of life - every conversation seemed to be provocatively examining life - how we assign importance, what is success, how do we view others based on how they present themselves to us etc etc. While empty in true characterisation, I thought every character was emotionally complex in the window we were given of them via Faye.

I was interested in reading Cahokia Jazz but maybe not so much anymore! There is, luckily, too much good stuff out there to compromise on to read something full of cultural blindspots!