I had an unexpectedly fantasy-heavy month in May, though my favourite book of the month was easily Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost, a book I could have started from the beginning again as soon as I finished it.

Before we get into the rest of the post, a quick note to say I’m sorry I dropped off the face of this Substack for a couple of weeks there! It’s been a bit busy round these parts and I’m yet to figure out a whole new research, reading and writing routine for my upcoming posts. Thank you for bearing with me. This month I’m going to finish my first speculative fiction round-up of the year, so keep your eyes peeled for that towards the end of June. I’ve got my list of books, I’ve got my ARCs downloaded, I’m ready to go. I’ve decided to do a few parts to this series so I can cover as much as possible.

This round-up marks the first instance where I write a post like this one without an accompanying YouTube video. If you are a fan of the video round-ups, I will make a big May and June video in a few weeks time.

Onto the books…

the great

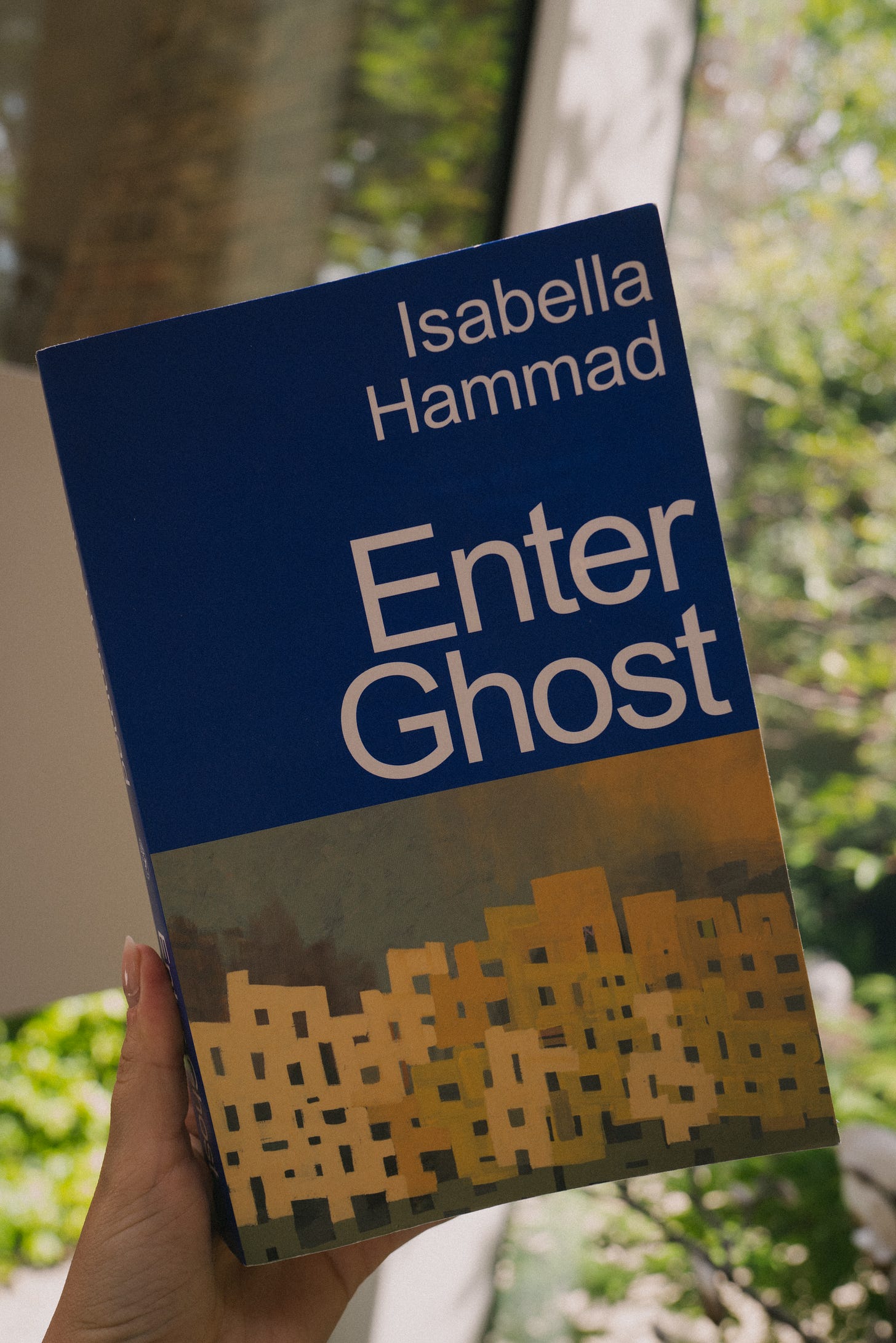

Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad

This is an excellent novel. And because it’s an excellent novel, I’m going to struggle to summarise exactly what makes it so excellent.

In it, we follow Sonia, an actor approaching middle age and recovering from a messy affair with her most recent director. She decides to leave her home in London and head to Haifa to stay with her sister, recalibrate and lick her wounds. Whilst there she finds herself drawn into a performance of Hamlet in the West Bank.

The book is narrated by Sonia and I was quickly sucked into her voice. I have been referring to this kind of prose as still water prose recently. It is fairly straightforward to read at a sentence level, sometimes conversational and perhaps even a little reserved emotionally. But this belies the hidden depths of this narrative, and in fact the great emotional force within. A little like the quiet surface of a deep freshwater lake versus the complex ecosystem beneath (simile now complete). Now and then you’ll find a sparkling sentence in this novel which brings to life a tiny detail of a fellow character’s body language, or perhaps the atmosphere of summer in Palestine. For some reason this small section keeps returning to my mind’s eye from just the opening pages of the book:

Where the wall curved on my right, a group of boys stood in a line. All elbows, hands on hips, shifting their weight from leg to leg, watching each other, waiting. Two were small and skinny, barefoot, with brown sunlit shoulder blades. Most of the older ones wore sneakers that left dark marks on the stone, and necklaces of drops fell from the seams of their shorts. The first in line took a running start and leapt, knees up. He seemed to fall for a long time, his body unfolding. Then he cracked the water and disappeared. When his head bobbed up again, the other boys didn’t react. I guess I was expecting them to applaud, or something. The diver flicked his hair and swam for the rocks.

We’ve almost all seen this group of boys by the sea, running and jumping into it, almost aimlessly it seems. Something about this passage captures that ennui of a long summer day. You can see the conversational tone Sonia takes with us: “I guess I was expecting them to applaud, or something”, and also the minute and beautiful detail which really brings it to life, the flicking of the hair, the shifting from foot to foot.

Whether she’d like it to be or not, Sonia’s life is highly politicised purely by virtue of being Palestinian, and this novel naturally explores the relationship between the personal and the political (“Must every Palestinian story be a family story?”) Her family is also from Haifa, now inside the boundaries of Israel, which brings its own particular selection of fraught identities. Sonia has a tricky relationship with Palestine and the trip detailed in the book is her first in twelve years. Partly, we gather, from heartbreak; not wanting to emotionally engage with a place that is constantly being lost, a place of humiliation and pain and decades of trauma. For Sonia, it has been easier to just disengage.

This book is testament as to why fiction in particular can be such a powerful way of learning about another place. I learned a lot here about relationships between Palestinians in all their different statuses; inside and outside the boundaries of Israel, in the West Bank, whether they were made refugees during the Nakba or are in the process of being expelled from their homes now, or are living uneasily alongside Israelis. Gaza and Gazans are mostly left out because, as Hammad has said in interviews, they have become almost completely isolated in the strip because of the occupation. The nuances here, the way Hammad has her characters interact over these differences—either in words or in silences—probably gave me far better insight than had I read the facts of it.

Hammad is able to bring a lot of these disparate parts together in her use of the play form, and the performance of Hamlet which the whole book is working towards. It naturally gives the book focus and a good teleological thrust. At times it slips into playtext, which as a former drama kid, I loved. In general returning to the world of theatre—another artform I am keenly interested in and kind of minimally informed about, at least compared to visual arts—was a wonderful addition for me also.

Alongside all this Sonia reflects on her childhood trips to Haifa, her life in London, a previous marriage. It is an inward-looking book in many ways (and a great character study), and yet Sonia’s actorly attention to others brings a precision to her observations that prevents it from becoming too insular. It is also a book about family dynamics, about friendship, sisterhood, community. It is a book about finding these things again after a time of feeling lost and aimless and hopeless.

You can see that Hammad covers a lot of ground with this book, and it could so easily have slipped out of her control. But her talent allows her to maintain a tight grip on her subject matter and themes. For me this is perfect example of a particular kind of literary fiction; it is not so challenging as to be unenjoyable or a slog or pretentious, but it is deeply layered and meaningful. She’s an author I will undoubtedly follow now through her career, and I’m keen to pick up The Parisian as soon as I can. This is a book I will no doubt return to (possibly very soon for some essays I have in mind), and I highly recommend you read it.

the very good

Ship of Magic by Robin Hobb

As many of you know, I read and loved Hobb’s Farseer trilogy last year, and I knew I wanted to continue my Realm of the Elderlings journey in 2024. Ship of Magic is the first novel in the Liveship Traders trilogy, which takes us away from the first person narrative of Fitz of the previous trilogy and into a whole different part of Hobb’s world.

At first I very much missed Fitz. In case you haven’t heard me ramble on about Hobb in the last year or so, this is rich, warmly written fantasy. It is not overly magical, but opts for a more psychologically real and sometimes political bent. The magic system(s), though, are intelligent and well-articulated. Reading Hobb is like reading an elevated, adult (and often quite dark) version of the very best of what I read as a kid. It is measured and doesn’t gallop along—to some readers’ frustration—allowing Hobb time to really build your relationship with her characters and flesh out the world. It’s immersive and highly enjoyable, and there are also themes here to satisfy those of us who want more intellectual stimulation and a consistent, principled worldview (something that can’t be said of some of Hobb’s contemporaries…)

Slowly as I got deeper into the book, I became enamoured with the new set of characters we follow here. The main story revolves around the liveship Vivacia. She is about to ‘quicken’ upon the death of her current ailing captain, which means that she is about to become properly sentient and alive. Due to an unfortunate series of events and interventions, her natural new captain Althea is robbed of the ship by members of her own family. Her nephew, Wintrow, is forced to give up his happy life in the priesthood to help his controlling abusive father aboard the ship. At the same time we follow a somewhat psychopathic pirate, Kennit, who is attempting to gain control in the Pirate Isles. Woven into this story is an examination of slavery, power, patriarchy and class.

Whilst I had previously thought it was more or less fine to start The Realm of the Elderlings with either Farseer or Liveship Traders, after a few discussions in Book Club recently I think to get the full experience it is better to start with the former. With most authors in other genres I always say to start with their best work, but when it comes to speculative fiction series—especially a long one like this—I almost never regret going in publishing order. Not to mention it can be so interesting to see how an author’s writing develops over the course of the series. Although at first I missed the focus we get with Fitz in Farseer, I could begin to see some of the ways she has already matured as an author here. She manages lots of different threads of storyline really well, moving between the different perspectives with ease. No easy feat. I look forward to seeing this development continue and also finding out some of the answers to the questions I was left with by the end.

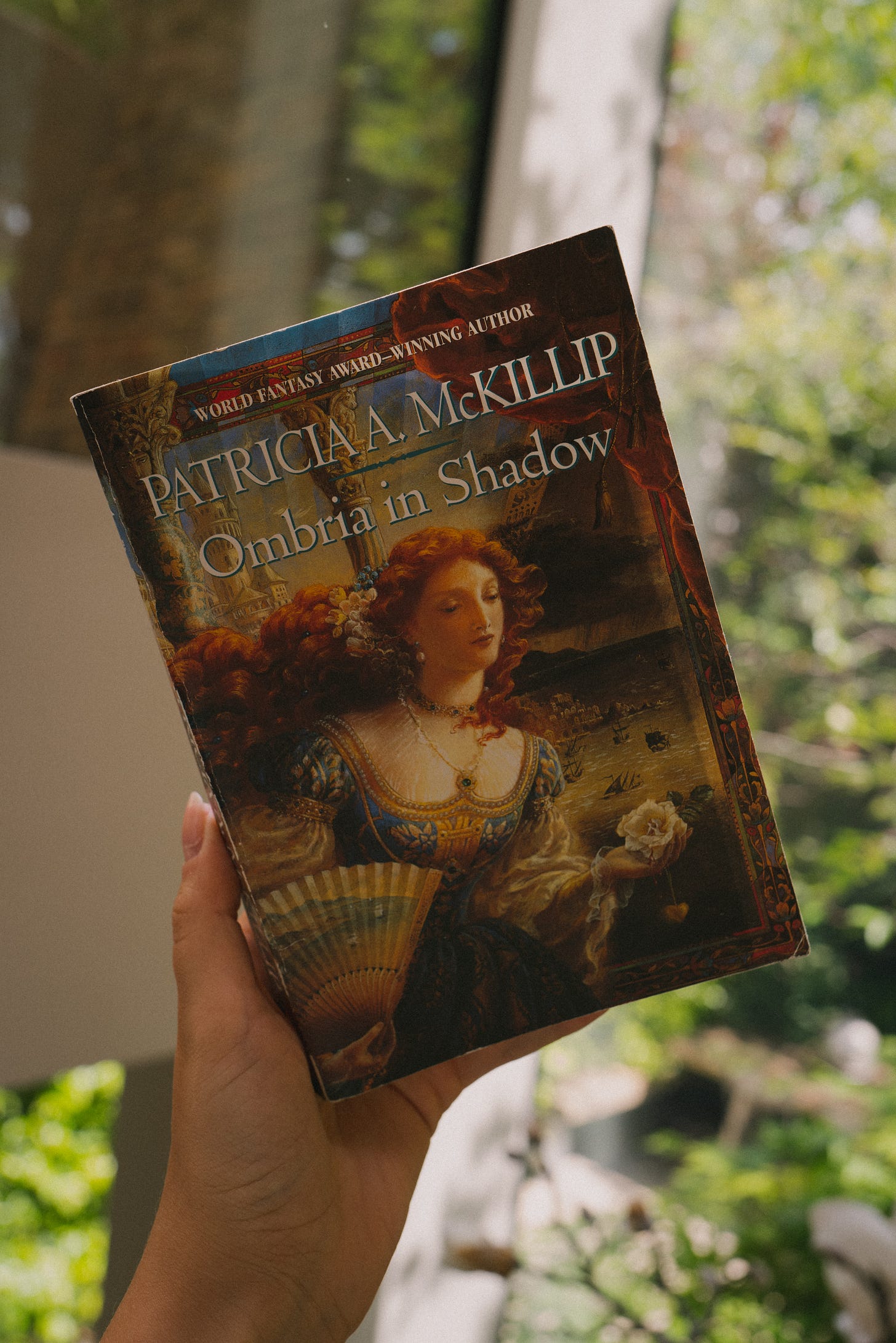

Ombria in Shadow by Patricia A. McKillip

Patricia McKillip is one of those authors who is much loved within particular speculative fiction circles, but rather unknown without. This was my first foray into her work, but it won’t be the last.

The city of Ombria is teetering on the verge of chaos. The Prince has just died, leaving the vulnerable figures of his mistress and five year old son in the hands of the irascible and terrifying regent Domina Pearl, a woman who has been around for far too long for it not to be by supernatural means. After kicking the mistress Lydea out of the castle, Domina attempts to seize control, but might she be stopped by another sorceress working in the underground levels of Ombria, Faey? A sorceress whose mysterious waxling, Mag, seems to have her own agenda. And what role does Ducon, the Prince’s bastard nephew, have to play in all this?

The prose is dreamlike and atmospheric. I felt a bit like I was looking at each scene through the bottom of a glass jar. In the centre of the scene would be one detailed focal image; elaborate puppets lying on the bed of a child, the charcoal-covered fingers of Ducon, sketching his surroundings. And then you get a kind of blurriness around it, a less sharply drawn atmosphere that allows for the magic to creep in when you aren’t looking. With the materiality and grounding of the central images, McKillip keeps you in the story where an even more dreamlike style would not, but she still creates that sense of fairytale strangeness overall.

These are not psychologically real, fleshed out characters, and yet it is in these little moments that they are made human somehow, despite their oddities. The pacing is a little up and down. McKillip was quite committed to writing standalone fantasy novels, and so at times this speeds through the important elements and might slow down too much in other areas. I would definitely recommend you read it in a few longer sittings rather than dipping in and out, as its easy to lose the thread of it.

Overall I really enjoyed this novel. It’s a fantastic example of a certain kind of fantasy which is more romantic and owes less to realism (compared to an author like Robin Hobb, for example) than it does to older kinds of stories. Stories which are more allegorical, more unknowable, more strange. A big thank you to Emily for bringing this to one of our Reviews in Book Club otherwise I never would have discovered this book. McKillip is definitely an author I will be reading more of in the future (I promise it has little to do with how beautiful the covers are…)

the good

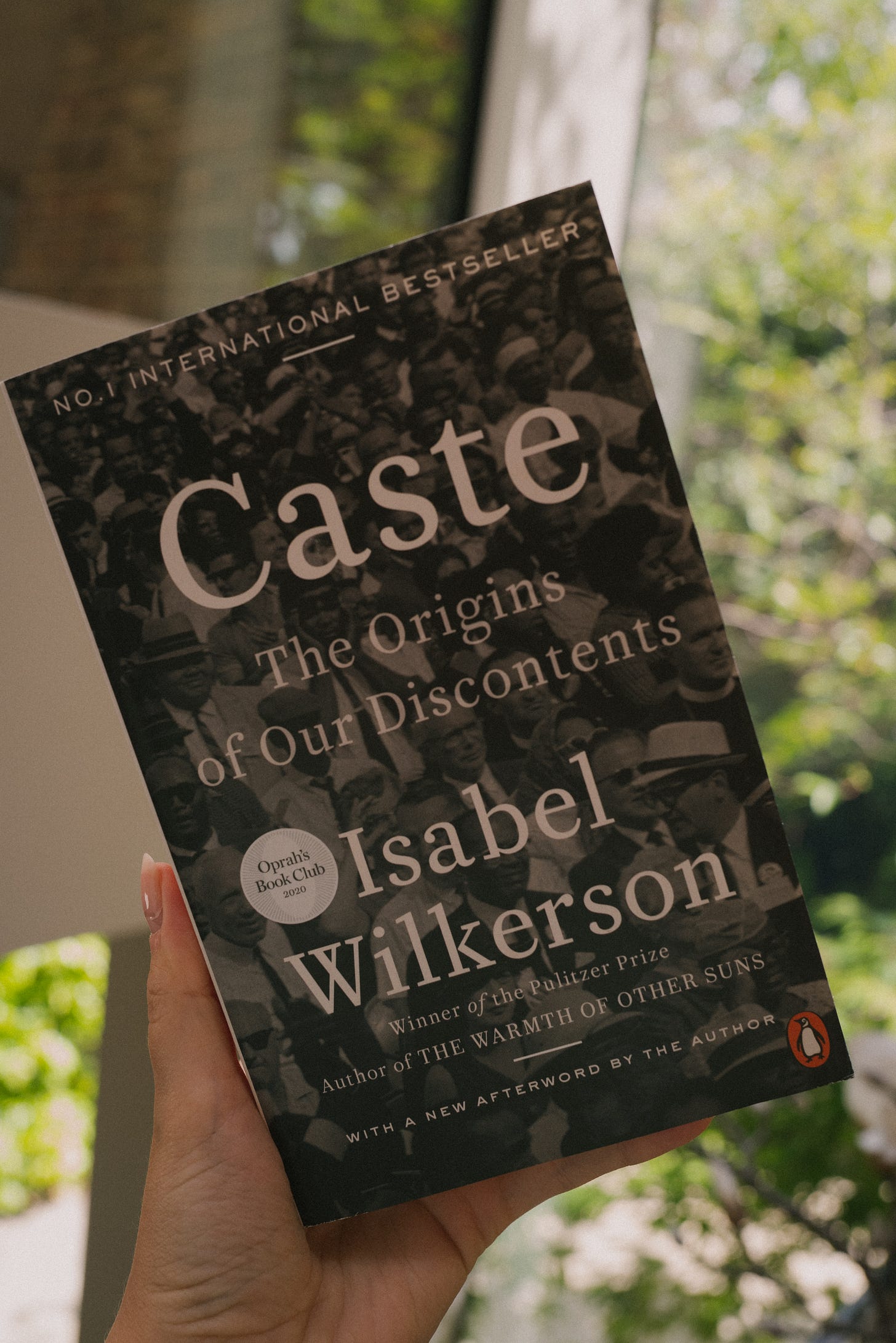

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson

In this book, Wilkerson adeptly explains how race and racism functions, how it is a completely socially constructed concept with no basis in biology (though this doesn’t mean it doesn’t hold real and damaging power, of course), and how we might think of its manifestation in the US as more of a system of caste, rather than race. She does this by comparing it to two other systems of caste, the Indian caste system and the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany.

I felt the opening section of this was great, and I think it would make a fantastic introduction for anyone having difficulty conceptualising how race can be a social construction and yet also wield real power and also sometimes have little to do with actual skin colour at all. As a journalist, she has real skill in breaking down academic discussions for a wider audience, and I do think this would make a great starting point for many readers. She is a narrative journalist, too, and I think she has a talent for picking out interesting stories and anecdotes to back up her arguments.

She lost me a little in the second half. She has a tendency to write too much and repeat herself (which I also found with Warmth of Other Suns). And yet at the same time sometimes some of the analysis was not quite as rigorous as a subject like this needs, especially when you pull in the caste system in India and Nazi Germany. I think the focus on the Great Migration worked well in Warmth, and perhaps she was just trying to cover too much in this particular book.

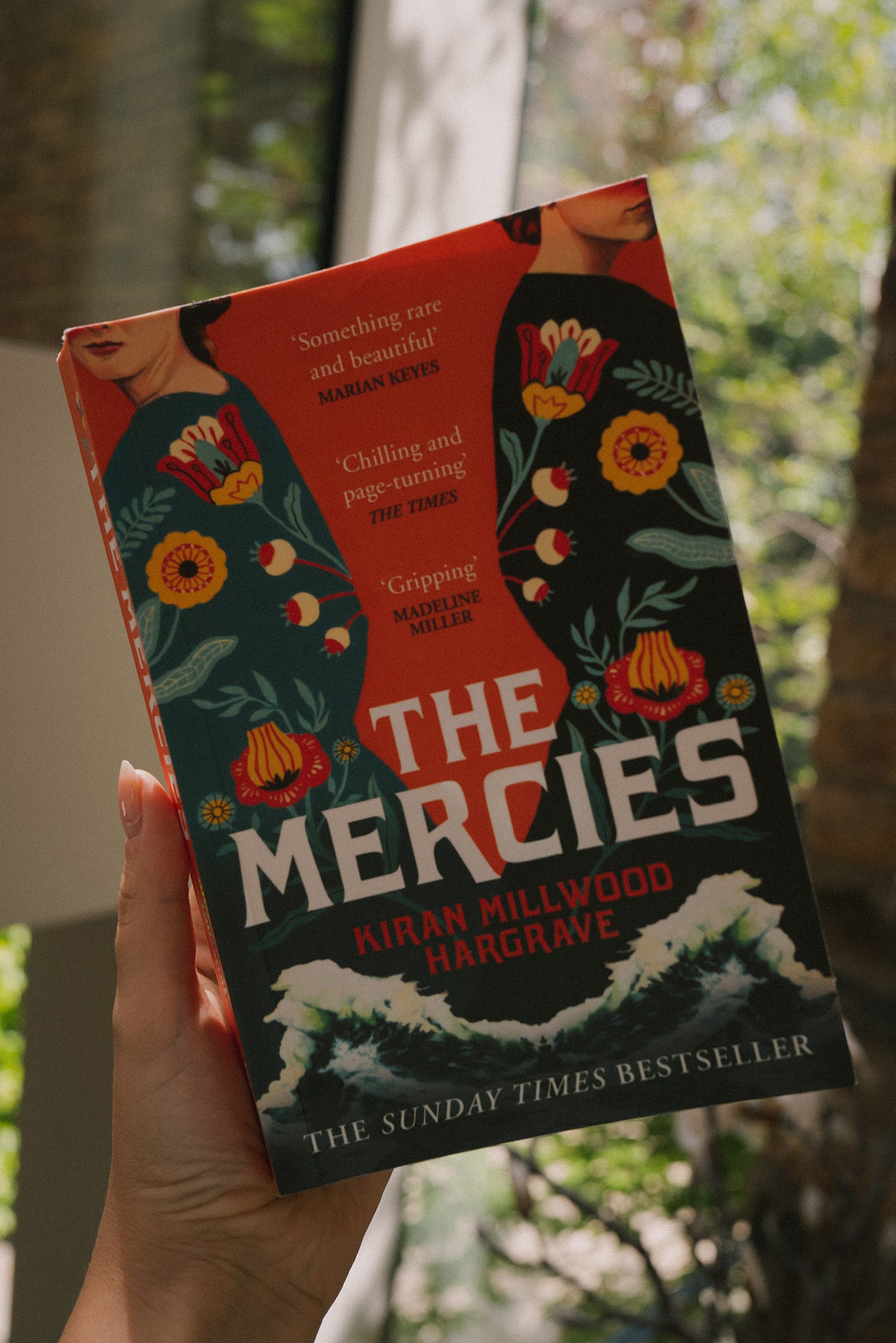

The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

This was our June Book Club pick, and you can see it wasn’t quite as successful for me as the previous few (that’s alright, you can’t win them all). In it, Hargrave fictionalises an account of the witch trials of Vardø in 1621. A few years before, a huge storm wiped out most of the men in the settlement, and this is what set off a chain of events that led to the trials and executions of a number of women and Sámi men.

We follow two protagonists; Maren, who has lived on this island her whole life, and Ursa, a young woman from Bergen brought here by her controlling and dominating husband, a Scot with a keen eye for ‘witches’. This is ultimately a love story between these two women, who find solace and comfort in one another in a harsh and difficult place.

Let’s start with the good. I think Hargrave handles the love story sensitively, and the tension builds solidly throughout. I think this will disappoint dedicated romance readers but for those of us who err on the side of the literary I think it works. The story was compelling and well-told. Hargrave has a background in children’s literature and I think you can tell in the fact that the story progresses well (though some of my fellow readers felt she left too much to the end).

Much beyond the story level though, I think it falters. I think most of us wanted to see more of the women of the island and how they collectively grieve and look after one another in the aftermath of this catastrophic event (and presumably how this ultimately turns to spite and denouncements). There’s another, much tauter and more rigorous novel somewhere here. Instead we are sped along to the arrival of Ursa and her husband and the impending trials. It would have been nice to see the romance be between two of the women of Vardø, for example. She toes a fine line with her Sámi character, Diinna, and mostly gets it right, but it would have been nice for her not to be relegated to the side of the narrative. By the end, there are a few things left unaddressed in favour of speeding through the trials themselves. One of my all time favourite novels is Jane Smiley’s The Greenlanders, which I couldn’t help comparing this one to, so I think it probably suffered for me in that respect. I’d maybe read more Hargrave, but perhaps a few more books down the line.

the fine

The Light Fantastic by Terry Pratchett

Here Pratchett and I are again. There are some authors and some worlds that my literary knowledge feels incomplete without. You may be surprised to know that I include Terry Pratchett on that list, but as a devotee of speculative fiction I feel it’s my duty to familiarise myself with Discworld and see if I like his work. And as I explained above, I’m a publishing order kind of woman, so I listened to The Colour of Magic recently and now have listened to this, the second Discworld novel (in a series of like forty plus). But I have been assured that these two are not representative of his overall body of work and that he improves vastly in subsequent novels. There was at least an overarching plotline to this, though the two protagonists do still skip from dilemma to dilemma throughout. Initially I was quite swept up in it but this quickly dissipated. I’ll keep you updated.

And that’s all, folks! Have you read any of these? Did you enjoy them?

If you’d like to join us over in Book Club, you can have a little look at what it involves here. It is easily the best thing I’ve done on the internet.

Thanks for reading!

Loved reading your thoughts on Enter Ghost. I read it last year and I loved it so much it’s on my list to reread some time soon (I hope). Have you read her debut novel, The Parisian? A very different story and approach but I loved that one too.

I have been wanting to read ‘Enter Ghost’ for a few months now and this review has just made me immediately order it - I have absolutely been influenced. I chuckled at the opening line of this book was excellent so now I have no idea what I’m going to say (incredibly relatable. for the record - you did a fantastic job of communicating just how excellent it was).

I adore the way you describe Hammad’s writing as ‘still water prose’, so gorgeous and basically poetry? I can understand exactly what you mean. There’s nothing quite like reading a book which describes the atmosphere of the summer, in the summer. Incredibly high praise from you calling it perfect literary fiction, and as a literary fiction enthusiast, I can’t wait to see if this comment holds up (I’m sure it will).

I also appreciated your reflections on ‘Caste’ which I’ve debated reading for some time. A great reading month!