The Ups and Downs of Reading a Shortlist

Reading and reviewing the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize Shortlist 2024

This post is too long for email, so do read in your browser or app.

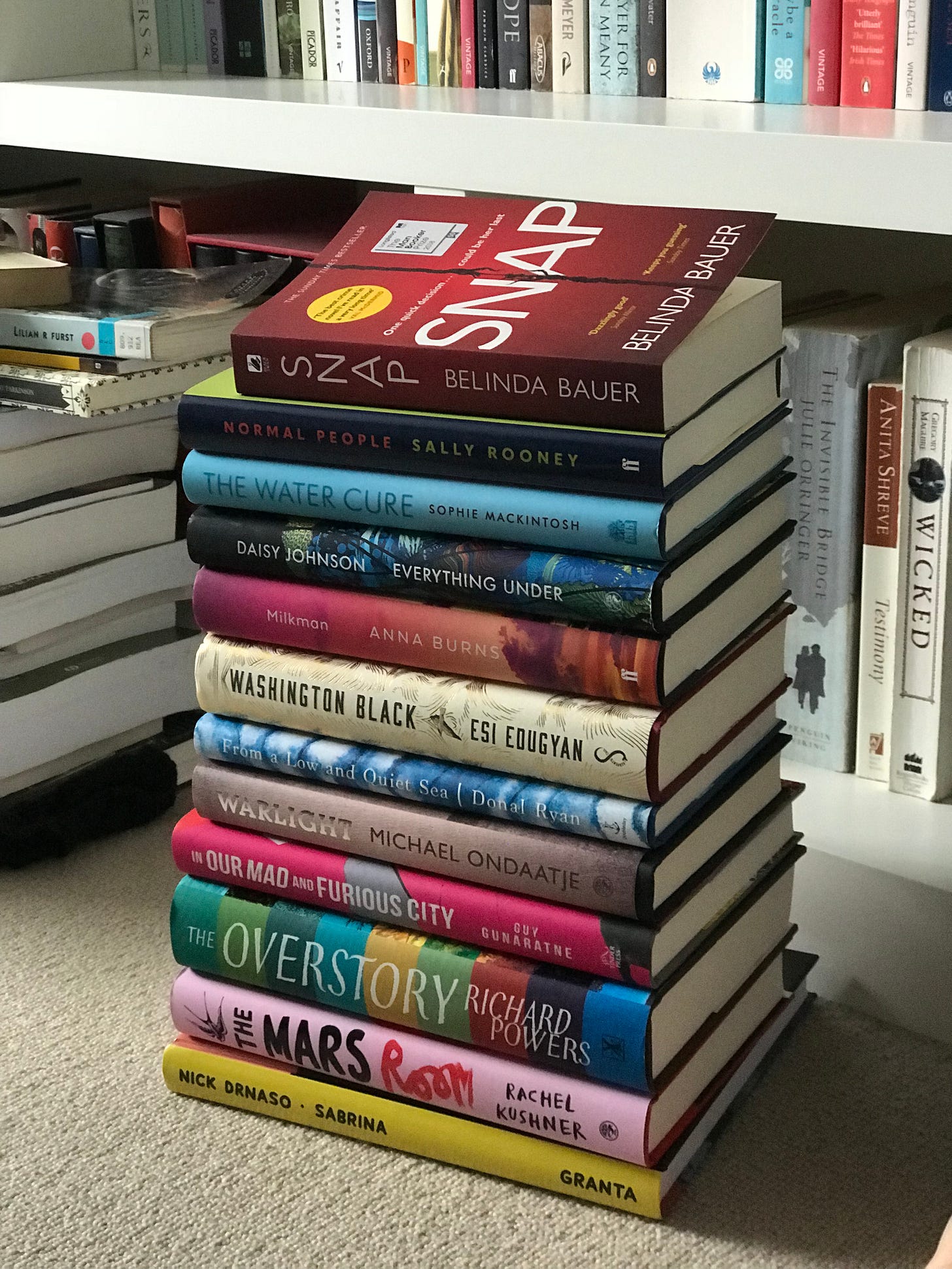

Fresh out of my Master’s in 2018, I walked into the Waterstones in Notting Hill and rather impulsively bought almost all the books from that year’s Booker longlist. I think one of the booksellers there was a bit annoyed that I had disturbed their Booker display (sorry). When I got home I decided to finish the job online, leaving me with twelve fresh shiny books staring at me from my shelves. I don’t remember a lot of online longlist reading at the time (though I may not have been looking in the right spots), but it has seemingly grown and grown in popularity in recent years. I think I was inspired to do it then because I had read and been impressed by Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, and written a whole dissertation on Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings, both of which had won the prize in recent years.

It took me a long time to actually finish the list (well into 2019 I think), and it was by turns rewarding and frustrating, as these things always are. Thankfully at least, I absolutely agreed with the judges that Anna Burns was a deserving winner with Milkman. Unfortunately, this hasn’t happened much since, with the exception perhaps of The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida in 2022. Tsitsi Dangarembga was robbed of the prize in 2020, and Anuk Arudpragasam in 2021… But I digress.

I have given up on the Booker in recent years, if not entirely in reality—I do tend to read one or two from the list every year—at least in my soul. I don’t expect them to highlight the best in literary fiction anymore, and certainly even if they list a good’un (My Friends by Hisham Matar being this year’s casualty), they aren’t going to crown it the winner, or even shortlist it.1 For now, I’ve turned my attention elsewhere.

When the Ursula K. Le Guin prize shortlist came out earlier this year, I found myself pulled to it. Le Guin is one of my all time favourite authors. I absolutely love her work and have been reading my way through it over the past several years after finally picking my twenty-year-old copy of Earthsea off my shelf in 2019.

The prize—begun in 2021 by Le Guin’s estate after her death in 2018—is given annually “to a writer for a single work of imaginative fiction”. I believe their definition of “imaginative” is much like how I use “speculative”, as certainly all the books listed have a speculative element. But something I really loved about the approach is how the list spanned both the literary and genre-based offerings, something which I obviously try to do over here.

Reading for this and my recent speculative fiction round-up means I have read a lot of contemporary speculative fiction these last few months and phew… it’s been a journey. Again, by turns rewarding and frustrating. I confess I am a little relieved that I’ve finally reached the end of these reading projects, and I’m ready to go back to a more balanced selection of genres moving forward. But as with my literary Booker experience of 2018-9—when I was introduced to the work of Richard Powers, Anna Burns, Rachel Kushner, Sally Rooney, Sophie Mackintosh—I feel like it has given me a grounding in this generation’s speculative authors, and an idea of whose books I should be on the lookout for in the future, whether I particularly liked the specific book listed or not.

So let’s get into the books. I read and reviewed Orbital earlier this year, and as I’m sure you know I didn’t like it much. Book club folks are most certainly sick of me banging on about this so I won’t go into it again, but I was glad to see that it didn’t win this prize as well. (Shall I briefly say I did plan to write this before the winner was announced in late October… and here we are in early December… honestly I don’t think that’s too bad for me!)

I also DNF’d a couple books. I did briefly wonder if I should push through in the name of completionism but then thought literally no one has asked me to do this. And the DNF is judgment enough in some cases. Some Desperate Glory opened with an intergalactic space war action sequence and my body just screamed no. I can tolerate some military space war style stuff—thinking of Cixin Liu’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy—but I feared it would be too much of a core component here. I think it’s about a protagonist who de-programs from a deeply harmful fascistic ideology which… sounds important! But yeah, the prose style wasn’t doing anything for me at all, felt like YA, and I’m wary of lots of action-packed scenes. This did actually win the Hugo this year, and if someone I trusted read it and loved it, I would consider trying again. But a hard sell for me. Her Greenhollow duology is supposed to be good.

I also gave up on Premee Mohamed’s The Siege of Burning Grass. This is a book of ideas, but not much storytelling whatsoever. It quickly became repetitive and had one of those world-builds/major themes you could explain in one sentence. Too tiresome to continue with! I’ve heard her shorter fiction could be better.

Onto the ones I did read…

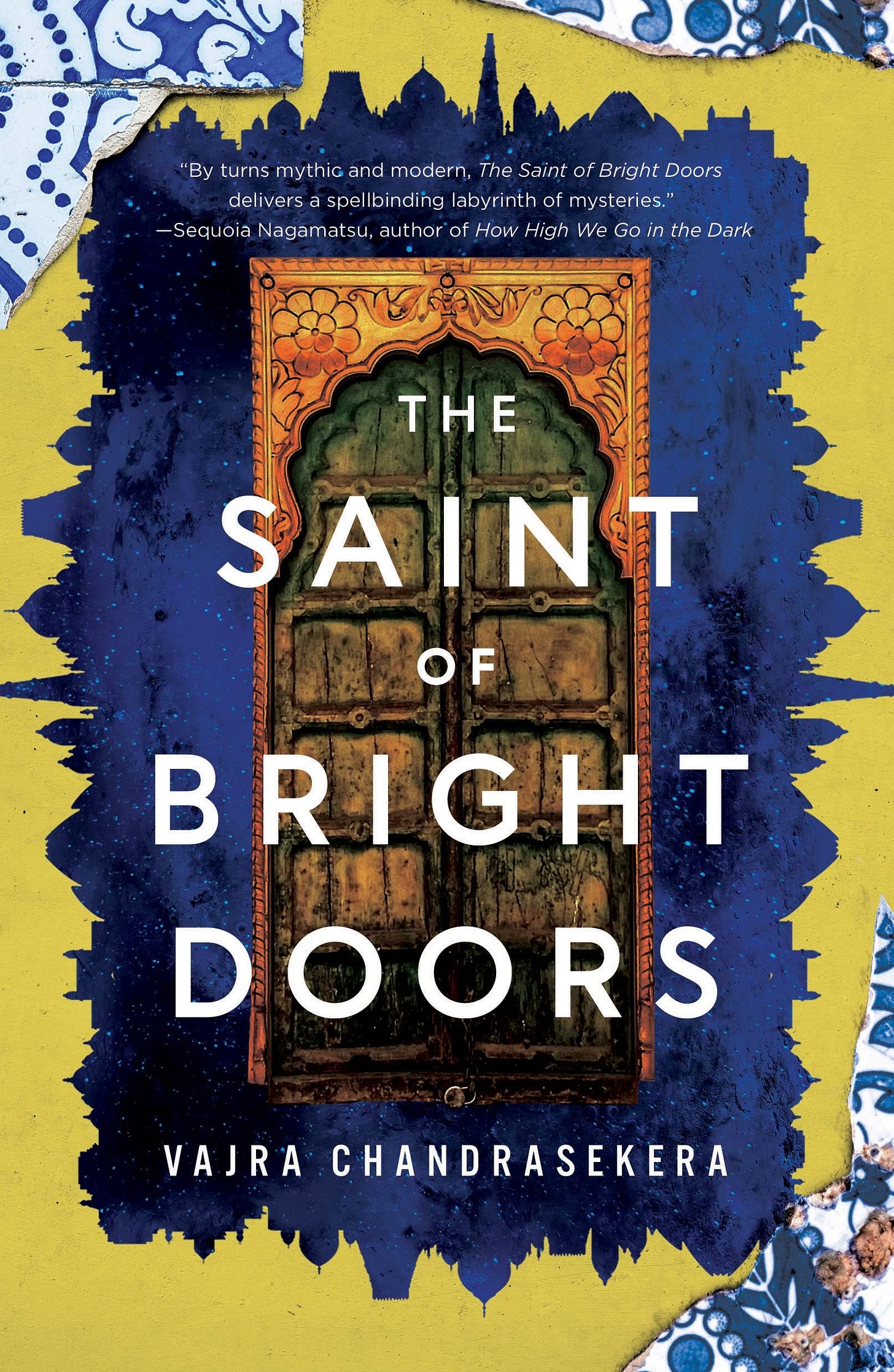

The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekera

Lots of potential, but not quite there with this debut. It opens with a punch; Fetter’s mother rips away his shadow at birth, leaving him with some strange abilities. He can see demons that are invisible to even the most powerful magical persons around him, and he can also float, being less tethered to the ground than us shadowed folks.

Chandrasekera is a Sri Lankan novelist, and I believe the imagery and environs of his home inform this book, as well as its relationship to India and its history with colonialism. The best thing about the book is when Chandrasekera really pushes deep into his imagination. Some of the imagery here is truly striking; I can still see some of the devils in my mind’s eye. When he is working at his weirdest, the novel is at its best.

There were a few aspects to the world-building that I also found really surprising and delightful, which is a tricky thing when there is so much trope-ification going on in this genre. But unfortunately it flounders a little, especially through the first half once Fetter leaves his village home for a big city, a place filled with mysterious bright doors that don’t open and seem to lead to nowhere. It’s one of the books I’m filing into that category where the concept is great and the potential is all there, only for it to get stuck doing fairly mundane things for tens of pages. And look, I love a little mundanity, but sometimes you can just feel when it’s the author stalling, or doesn’t know quite how to handle some of the more ambitious parts of a book. I would be surprised if you didn’t walk away from this one disappointed over how it resolved these mysterious bright doors and the world that potentially lives beyond them.

The city Fetter goes to has aspects to it which would make it very familiar to you and me; gods proliferate, but they use viral marketing and crowdfunding to grow their followings. When the plague appears, people go into lockdown. In some aspects, like with the latter, Chandrasekera has interesting insights. And a plague seems to fit better in this world, conceptually. But as for the more internet-y stuff, I can’t help but wonder why these things are injected into this world except to give it a sense of relatability perhaps? To help us recognise more clearly what Chandrasekera wants to tell us about our own world? Or to write another kind of novel in amongst the broader frame of fantasy; a more insular and intimate one of a twenty-first century man just trying to find his way? The problem is it doesn’t quite succeed in this—I don’t think we ever quite warm to Fetter as we should, I don’t think this is Chandrasekera’s strong suit—and I always just wanted to return to the more mysterious, arcane aspects of this world, where he is on stronger footing as a writer. Other people do the insular, intimate thing better, only he can write about this weird and wonderful place.

This is a debut novel, though, and I think we put too much pressure on debut authors to nail it first time around these days. Ultimately I’d be very willing to try more of his work in the future, so I think that’s a good sign. He came out with a book called Rakesfall this year, and it’s on my list to try.

The Skin and Its Girl by Sarah Cypher

I really wanted to love this novel but unfortunately it missed the mark for me. We follow Palestinian-American woman Betty, who has returned to her beloved Aunt’s grave to ask for her advice. She wants to know if she should leave her family and follow her heart and the woman she loves to another country. Interesting thing about Betty: she was born with cobalt blue skin, a nod to the soap factory her family used to own in Nablus before it was destroyed in an Israeli air strike, where they produced luxurious soap in the same hue.

What follows is Betty telling the story of herself, her Aunt Nuha, mother and grandmother over the course of the last few decades. As it is addressed to her aunt, she uses second-person “you” a lot. Whilst I’m usually okay with this, for some reason with this particular selection of women I found myself getting confused, especially in the early passages where Betty is just a baby. It was easy to get jumbled between the different women when our protagonist is not technically a fully conscious presence in the scene she’s describing.

This novel is just way too long, and it had a distinct lack of focus, especially in those early sections. It didn’t feel confidently handled. When she was a little older (though she is a baby for a long time), I did feel there was at least some focal point that the book could coalesce around, now that the narrator could participate in the memories she described. I wonder if Cypher should have either told Betty or her Aunt Nuha’s story, rather than try to do a strange, unbalanced mix of both. It reminded me of Disoriental in style; a story told retrospectively from an important juncture in a protagonist’s life which also deals with their ancestral history and close family members, switching between lots of different mini stories and scenes. Though I found it a solid read, I didn’t love Disoriental, and I felt that this one had the same problems but possibly even more exaggerated.

Also, the only speculative aspect to it is the blue skin, which is not really explored much at all. I am tiring of otherwise realistic books with this one ‘magical realism’ element. Too often it feels like an afterthought (I’m thinking of The Eighth Life which has something similar in the hot chocolate, and which I had to give up on recently).

There were some beautiful moments in here hidden amongst the narrative chaos, and I would be open to reading future work from Cypher on that basis, but I won’t be racing to get hold of it.

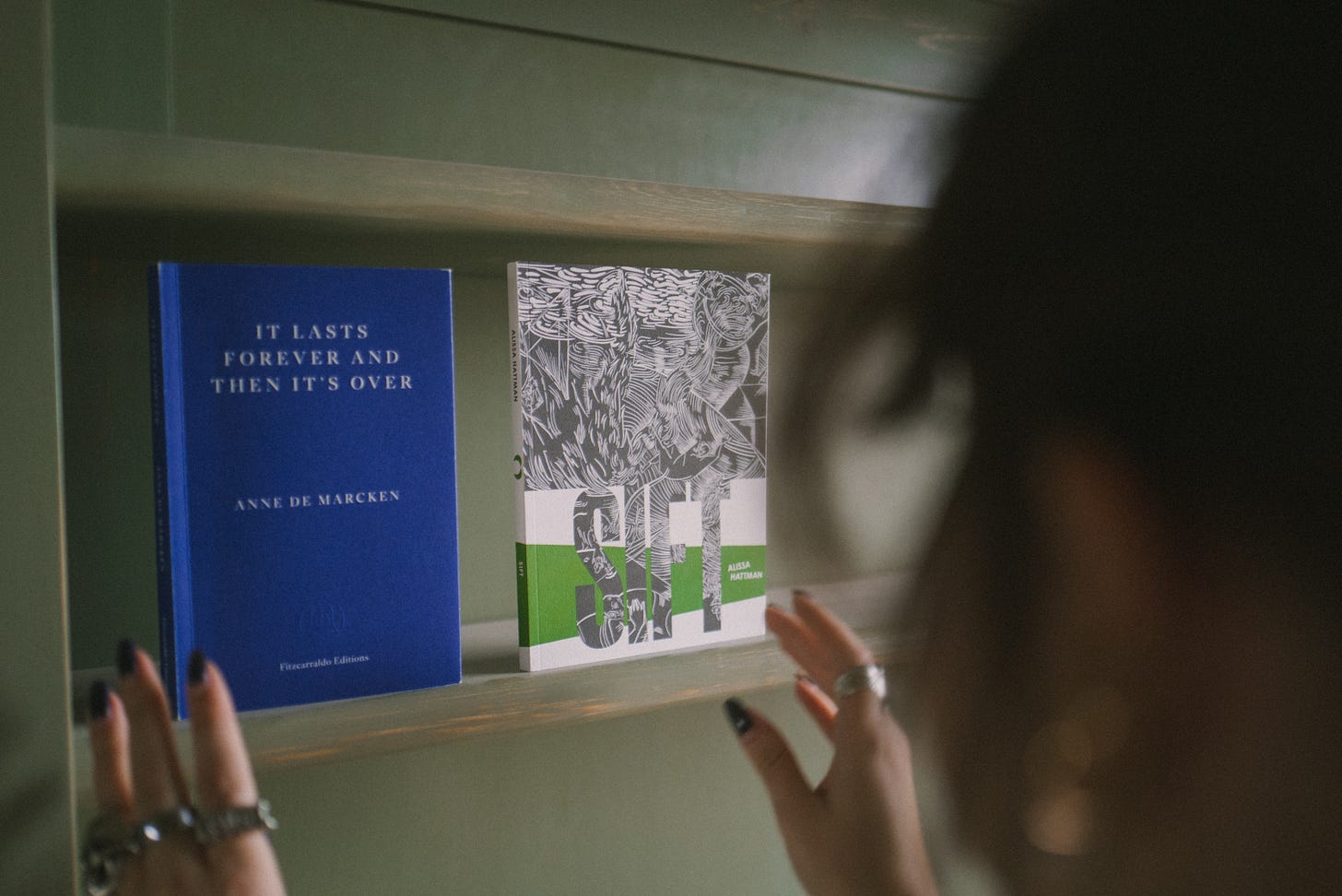

It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over by Anne de Marcken

Probably the most unconventional take on grief you’ll read, but somehow it totally works. Why unconventional? Because our main character is a zombie… or undead, if you want to be more dignified with it. Her arm falls off on page one though, so de Marcken is absolutely aware of the slapstick elements of the zombie figure, and I was glad to see that she didn’t shy away from this in her depiction. Particularly because it is the materiality and sensory elements of this book that keep it grounded and prevent it from losing the specificity and substance it needs to keep our interest. It is, after all, written in a fragmentary style, and plot is not the major draw, though we do follow her on a journey away from the city she starts in, and there are various identifiable events throughout. But the focus is really on the profound sense of emptiness and grief our conscious zombie exhibits.

She knows that she is missing something, someone, but as she’s lost much of who she was before her zombification, she doesn’t know who or what that is. Perhaps it is simply her humanity itself. Perhaps she recovers part of it on the journey. The slight tonal shifts between the black comedy and the quiet reflective work well to provide balance. It is surreal and strange and moving. Touching on the deep unending void that grief can be. I recommend you read it in one or two sittings to feel its cumulative effect. I will be returning to it myself, I suspect.

Sift by Alissa Hattman

This is by far the most poetic book on the list. Almost to the point where it’s difficult to describe exactly what happens in it beyond this: we follow two women as they journey across a landscape ravaged by ecological disaster. They end up inside a mountain, where they begin to transform into something unrecognisable even to each other. We get a little backstory of the speaker’s life—particularly her difficult relationship to her mother—and her travel companion’s resistance to her bids for intimacy.

This book imagines a world after humanity, or perhaps when humanity has becomes something other, more alien to itself. In that way at times it reminded me of The Doloriad, with strange elliptical conversations and a splash of the grotesque (though perhaps not quite to Missouri Williams’ levels). And as with The Doloriad and It Lasts Forever, it is strange and surreal, but without the materiality and plot footholds of the other works. It is far more abstract in style. I think it will absolutely work for readers who like this kind of book which is more akin to prose poetry rather than a novel in the traditional sense (and after all, the prize only stipulates it need be a “singular work”, not necessarily a novel). Read this way, I think it’s successful at capturing the feeling of apocalyptic dread that accompanies climate change, and the otherworldliness that might be in store for us. Here is a slice to give you a taste:

Our discoveries are fleeting, paper-thin—they will not be remembered like this. But maybe by moss, by water running down the stone walls inside of mountains, maybe in gypsum on the bottom of oceans that are gone and the ones that will come after, wave upon wave of chalk dust. And in the landscapes of our minds—our overactive, oversensitive minds, that will continue to interfere with all that is necessary for our survival. So be it. We know no other way.

When all is said and done, let the wind and water continue to transform the earth without us.

Let us be but a breath.

The Library of Broken Worlds by Alaya Dawn Johnson

At a sentence to sentence level, this is up there with one of my more challenging reads of the year, simply because of how alien it is. Published by Scholastic, it has been categorised as young adult fiction, but I think it could easily be considered standard adult fiction, and I’m not sure many young people would battle through this one.

Set at least 10,000 years in the future, we follow an AI called Freida, born in the bowels of a library god, on a planet made entirely from library. As one might expect from a civilisation thousands of years into the future, this place is almost totally unfamiliar. First of all the library is not the kind of place you are picturing. Being an entire planet, it has many natural features like cenotes and waterfalls, meadows and woods. At the same time the characters interact both physically but also through internet channels and avatars. Over the course of the novel, Freida must discover who she is, and also uncover a historical crime that led to the founding of the library, a crime that has resulted in hundreds of years of oppression for peoples all across the galaxy. Sadly, I could think of many real world equivalents as I was reading; Johnson knows exactly what she’s doing here.

The novel is overtly political, and following the different factions, planets and peoples is the first tricky step in amongst all the super-future jargon. You’re navigating an alien legal system and hundreds of years worth of history. It was so dense at times that it was difficult to tell whether I wasn’t quite up to its ambition (especially on a first read), or whether there were issues with its pacing and storytelling. I imagine it’s a little of both. I do think it will feel clearer with a reread. But in general I had to really admire Johnson’s work here. She fully committed; the world is sufficiently strange for something set so far in the future and there were some truly surprising elements to it, also. It was deeply layered and thoroughly conceived of, in ways I hope all speculative fiction authors reach for. But I can’t imagine many people I could successfully recommend it to.

Those Beyond the Wall by Micaiah Johnson

I was really struck by this novel’s opening pages. I was instantly taken in by the narrative voice of ‘Mr Scales’, a mysterious character who immediately acknowledges her own slipperiness as narrator. In the first few moments of the book, she witnesses the brutal death of one of her closest friends. Part of a sort of criminal dynasty, she is then tasked by her superiors to find out who is committing this selection of strange perpetrator-less murders, of which this is only the first.

This is the second Ashtown novel, and I actually tried the first a few years ago for review, but wasn’t particularly gripped by it. In both books, the immediate world is divided in two; there are those that live difficult lives in Ashtown in the searing desert, and those that live in a comfortable biodome in Wiley City. I definitely think Johnson has matured as a writer in the interim, and I was impressed by her world-building, characterisation and vivid imagery. For the most part I was happy to keep reading this one, though I think it got a little slow and repetitive at points, and there was perhaps a touch too much angst in our protagonist. You know when they have a chip on their shoulder but it just goes too far to be believable? Anyway, yet another on my long list of books recently which was just that bit too long. Overall, though, I think Johnson has a good grip on what makes a good story, and I’d be interested to see what she writes next.

The Singing Hills Cycle #1-4 by Nghi Vo

Only one of the latest instalments of Nghi Vo’s Singing Hills Cycle, Mammoths at the Gates was listed for the prize, but I decided to listen to the three prior novellas as well to catch up. I found it difficult to listen to these as they are gentle stories with quiet reveals, meaning if you aren’t fully focussed you’ll miss them. The lightly lyrical style compounded this problem, so be warned!

I am glad I made some effort to catch up though because I think Mammoths at the Gates was actually the best of the four, but also required a touch more background knowledge. Is it also because I read it properly rather than listened? Possibly, but I think there is more to it than that. Whilst the previous books also follow Cleric Chih as they travel a fantastical Southeast Asian inspired world as an archivist and recorder of stories, the fourth instalment follows them home to their Abbey, where another beloved Cleric has just died. I thought it was a really lovely story about grief, about what makes up a life and what must be remembered, and how to reckon with somebody’s full self and legacy. The more personal element—the fact that the story is about Chih and their home instead of someone they meet—made it more impactful for me and I was glad I had familiarised myself with them already. Read if you are in the mood for well-written bitesize fantasy.

Conclusions

In case you’ve made it this far without finding this out, the prize was awarded this year to Anne de Marcken for It Lasts Forever and Then Its Over. I think she is a very worthy winner, especially from the more literary entries on the list. It is a beautiful, imaginative take on the classic zombie/undead story that really does add something new and fresh to that subset of fiction that deals in grief. I would absolutely read it again and I’d read more of de Marcken’s work in the future.

I think I would also have been happy for The Library of Broken Worlds to win from the more genre-based offerings, mostly for its sheer ambition even though I spent much of my reading a little confused. I actually don’t know how Johnson managed to pen that book and keep it all together. Big-brained stuff.

I’d definitely recommend Nghi Vo’s Singing Hills Cycle if you are looking for peaceful, reflective fantasy. I also think The Saint of Bright Doors is worth checking out as I feel Chandrasekera could be an interesting author to watch (or you could try the new one). Read Those Beyond the Wall and Sift if they sound like your kind of thing (two books at the opposite end of the scale from each other!) Sad to say I’d probably skip The Skin and Its Girl; if I knew it was going to turn out as it did I don’t think I would have kept reading through all 350 of its pages. I do think there are other authors out there tackling similar styles and theming more successfully.

Would I do this again next year? Yes, I hope to (and with a bit more organisation maybe so it doesn’t completely take over my life). I read books I might not otherwise have picked up, and in the process expanded my sense of what can be done in these genres, and in fiction in general. Perhaps you’ll join me?

Another post coming later this week for everything else I read in November, including Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Jeff VanderMeer’s newest Southern Reach novel Absolution, and my first Jon Fosse.

Booker organisers if you’re reading, I’m happy to be corrected on this in the future! Literary critics, academics and career reviewers make great choices for judges!

I agree with practically everything you’ve said re the Booker! They’ve lost their touch. Since reading it I can’t believe My Friends didn’t make that shortlist!

I’m gutted to read your thoughts on The Skin and Its Girl - that has been lingering on my tbr for well over a year and I thought it sounded great? I did enjoy Disoriental thought so maybe I need to just give it a go if they’re similar.

I have a copy of It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over so I’m happy to see you singing its praise! I haven’t read a book about a zombie in a long long time and it’s a fantastical concept that I’m probably missing a bit in my usual genre rotations of frequently very serious stories.

Well done for reading the list! It can definitely be hard to keep momentum up when you’re doing it (I read international booker shortlist this year and by the end I felt I was going crazy and could not believe I’d subjected myself to it) I am definitely considering joining you for a few next year.

I can’t wait for your thoughts on 2666 (I’ve got my first Bolaño on my shelf (The Savage Detectives) to read soon) and your first Jon Fosse! I read A Shining earlier this year as my first Fosse. The experience of reading was something else - fascinating and confusing. I really want to read more of him though! I’m eyeing up Morning & Evening.

Thanks 😁 some more book to add to my tbr!