October 2024 Reads

munir hachemi, jennifer croft, ray bradbury, kei miller, ken follett

Welcome to one of my monthly wrap-up posts, where I briefly review everything I read! I read widely across many genres, from classics to literary to speculative fiction. With these I’m hoping to shed some light on backlist gems, perhaps push you to read outside your genre comfort zone, and also highlight which new releases are worth your time.

Hello, everyone! This wrap-up is looking shorter than usual as I’ve been reading primarily for my speculative fiction round up (on its way to you tomorrow) and working my way through the Ursula K. Le Guin prize shortlist which I’ll be writing about next week, all being well. Anyway, it was a very solid reading month; even if I didn’t enjoy everything I read I gained something from each.

Living Things by Munir Hachemi trans. by Julia Sanches (2024)

I had it in my head I’d be reviewing this for my speculative fiction round-up but about halfway through I realised that SF wasn’t the genre this book was playing with at all, it being more of a literary psychological thriller (and heavy on the literary at that). Perhaps it is horror inflected—at least by the protagonist’s own admission—but not in a particularly supernatural way.

The novel is set in that perennially useful could-be-the-near-future-but-also-could-be-now kind of time, as weird weather events begin to plague its characters. It follows four young Spanish men who travel to the south of France to earn some summer cash picking grapes. Only once they get there they realise there are no jobs among the grapevines at all because they’ve been washed out by the unseasonal torrential rains. But they can go and wring the necks of chickens if they like? Or vaccinate them? Or would they like to fatten up ducks?

As the summer wears on and the men restlessly move from job to job, they become increasingly disturbed by what they see. Through the strange otherworldly monotony of the early hours stamping their feet outside warehouses filled with petrified birds, Hachemi tries to “narrate the horror of real events”1; tries to show us that “true horror does not know vitriol, only monotony and routine.” The narrator (also called Munir) admits he and his friends are not really there because they have to earn the money, but rather to garner that elusive caché of ‘life experience’ that can only be attained by a bit of manual labour. For these middle-class boys, it is this that attracts them the most. Munir hopes he might get a novel out of it. But of course, it is the gap between their expectations (somewhat romantic vision of picking grapes) and the reality (using something that looks like a petrol pump to ram food down bird’s gullets) that produces this psychic disconnect and the horror of the piece. The novel progresses, and we wonder why they don’t just leave, especially as they don’t have to be there. But something of their machismo, the strange dynamic between them roots them there until the end of this disastrous summer.

As you might be able to tell from some of my quotes so far, fictional Munir does not shy away from giving us his direct opinions about late stage capitalism and his own experience of fictionalising this summer, writing it, processing it for a reader. This usually throws me completely out of the book, but here it generally really works, and the opening sections where our protagonist writes candidly about what we should expect from the narrative made for a deliciously fun unreliable narrator reading. It’s clear he is desperately anxious about what it means to exist in this world and then tell stories about it, in ways I know at least I can relate to. Hachemi’s ability to construct this believably through a strong narrative voice is a big contributing factor to the book’s overall success. I only wish he had maintained this energy throughout. Whilst this fundamental instability continues, I think I wanted Hachemi to have a clearer picture of what the disjunct between reality and our narrator’s experience is. That way, some of that mystery and tension that he builds so well in the opening section could be maintained, and as the reader I could have the satisfaction of puzzling some of it out.

Because it does lose steam about two thirds of the way through. I get it, we need a sense of monotony. But this is such a difficult line to toe. It’s a problem I see consistently in books of about this length. Could this have been a very successful fifty to seventy-page long short story and not lost any of its power? I think so. Could it have also been expanded with a bit of extra storyline support (it ends rather abruptly, for instance) to the tune of about two hundred pages? Also yes. It’s this sticky 100-120 page range that I think tends to be very difficult. Some stories are perfectly suited to this length, but many are not.

Overall, though, I was really impressed by this, especially as Hachemi’s first novel. I had an e-ARC from Fitzcarraldo (thank you!) and it’s surely a good sign that I plan to purchase my own physical copy. I absolutely think it would benefit from a re-read at some point to get into those early sections even more, as Munir tries to decide how to tell this story, the story of the disturbance of a mind, the story of late stage capitalism.

The Last Warner Woman by Kei Miller (2010)

‘Mr Writer Man’ just wants to tell us the story of Adamine Bustamante, a ‘warner woman’ (i.e. a diviner/forecaster) who grew up in Jamaica in the first half of the twentieth century before immigrating to England, where she finds that her warnings are received with suspicion and land her in a mental institution. But his story keeps getting interrupted by the protagonist herself, who is quite adamant that he is telling it all wrong.

Well, that’s my spin on the blurb anyway which has it the other way around, and which I found to be fairly misleading. I was expecting this to be a real clash between the two narratives. But instead this is more a story of healing and reconciliation. I don’t want to spoil too much, but I hope if you go on to read this now you’ll have a better sense of what it’s doing. I think the imaginary other novel that the original blurb conjured up for me did interfere with my reading experience.

This is one of Miller’s early novels, and there was a lot to like about it. I thought at a smaller scale the storytelling was strong, the voices were well-realised, the prose style was effective; poetic without losing narrative steam or getting caught up in meaningless turns of phrase. But I think the overarching plot line could have done with a bit more work; one of the main bits of feedback from our book club sessions was that we just wanted more. More of Ada’s childhood, more of her time amongst the Jamaican Revivalists, more of her time in England. So lots of potential, but not quite there in terms of the kinds of things that would make it really stick in your mind after your reading. I definitely want to read Miller’s Augustown, as I’ve heard very good things and I’m sure he will have matured as a writer since the publication of this.

The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft

Veteran translator Jennifer Croft writes fiction solely under her own name here, to mostly good effect. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it’s about the act of translation itself.

You know how I’m often saying I want authors to get weirder? Well, Croft needs no such haranguing. This novel is pretty wacky, and her willingness to push the reader gives it a real energy and scope that can’t be said of some of her contemporaries. It’s another that I originally intended for my speculative round up (coming in a day or two) but that ultimately didn’t quite fit the bill. However, the feeling and atmosphere of a weird novel is certainly here.

A group of eight translators gather in the Białowieża forest on the Polish-Belarusian border to receive details about highly-regarded Polish author Irena Rey’s latest work. There—where no outside opinion can reach them—they will translate this tome of a novel as they have done many times before. Only not long after they arrive, Irena goes missing. This novel is partly a pretty fun send up of the literary world; the moment when they discover Irena might *the horror* organise her bookshelves by colour absolutely elicited a chuckle from me. It is biting in tone and sometimes farcical as the translators—now like headless chickens without their all-powerful leader—try to find out what happened, and slowly become deprogrammed from the cult of Irena Rey.

But it is also intelligent and insightful, as only good satire can be. This borderland has both historical and ecological significance, and Croft deftly balances her different themes by choosing this setting. Mostly—and it seems she’s not alone if we look at her fellow authors Elif Batuman and Brandon Taylor just on this website—she seems concerned about the role of art (particularly this very insular, erudite literary art) in a world that is facing such huge political, social and ecological crises. What does it mean to create it, to dedicate so much time to it, and what kind of morality is at work in the figure of the author and the weighty literary tome? In this, Croft can marry themes of translation (partly the struggle for power across languages) with that of climate change—why write when the world burns, how to write about the world burning—and the particular strange politics at work in Białowieża.

The novel is chaos, which may or may not work for you. I can’t say I totally enjoyed reading it because just when you think you have a handle on it, it slips out of your grasp. However, I do think it is actually doing and saying interesting things, and Croft makes a set of choices with it that are consistent with what she is trying to communicate. This can’t be said of other less enjoyable/chaotic litfic. And so I certainly admire it. When it comes to literary fiction that really captures the current mode, I think this is a fantastic example.

The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert

American journalist Elizabeth Kolbert writes here about the current mass extinction we are living through—the human-engineered one—in comparison with the extinctions of the past. Each chapter covers a species that is under threat or already extinct and Kolbert travels the world to meet with scientists and those on the frontlines of climate change.

I learnt a few interesting facts from this book, and I found Kolbert’s style to be very readable. But I wasn’t sure exactly what she was trying to say here. It’s okay actually because so far in the Earth’s history there have been multiple mass extinctions and animal populations always recover, even if they’re different species from the last time? Or actually ours is bad because we’re the ones doing it and we shouldn’t be? Or ours is worse than others? The latter two options are hinted at but not entirely persuasively argued, leaving me a bit lost as to what the point of this book is. Maybe I’m just supposed to infer it without having it pointed out to me? But I would say there really is a kind of ambivalence to how Kolbert writes about it. Like why compare the mass extinctions if you don’t just a little bit think there’s something in the first theory. Perhaps I’m too familiar with the founding idea—that we are living through a mass extinction—in ways which 2014 readers wouldn’t have been, and that is really the driving force of the book. But still, it feels like just enough ‘oh no’ for those who’d like to pat themselves on the back for reading it, but not enough ‘oh no’ that they’ll be moved to action afterward.

The structure, too, feels quite meandering, and overall I’m not sure it’s a book I will be reflecting on for a long time. There are better books about these topics out there. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised it won the Pulitzer in 2014 (which I do realise is like ancient history for this specific topic), but I still kinda am.

The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett

This is generally very entertaining commercial historical fiction. I think because of its size (it’s over a thousand pages long) it often gets lumped in with more challenging novels, but as Follett writes in his introduction, this is a good ‘popular’ novel. It’s there for your amusement, not because it has integrated themes or a unique prose style or whatever else you might look for in something more literary. And as we’ve noted recently, good storytelling is hard to do, so this is a skill all of its own. That’s why the novel has been so well-received and why so many people have read it.

I listened to it and I just straight up enjoyed it, especially in the first half. It’s about the construction of fictional Kingsbridge Cathedral in 12th Century Britain. We follow a small cast of characters as they fight to get this cathedral built against all odds. I say in the first half because I liked the first set of characters best. I find with generational stories like this one, I tend to be much less interested in the progeny of the primary characters. They’re like the nepo babies of characters. I need authors to give me very good reasons to care about them beyond ‘they are this character’s child’… but I digress. This wasn’t the only issue for me in the second half. Having been written in the 80s by an author that mostly wrote thrillers, you might not find it surprising that there are a lot of gratuitous and graphic rape scenes. They are absolutely there in the first half (does anyone else find this ten times worse in audiobook form?) so be sufficiently warned, but the torture of our main female character really amps up in the second. Much of the drama seems to be from wrecking her life which I… did not love.

I didn’t even have to check with Google to know that this novel is not historically accurate whatsoever. Follett is not here to put us in the alien world of 12th Century Britain, not really. Not like Hild, or The Greenlanders or Wolf Hall. It’s like reading a nice BBC Drama. A little light on scene setting, high on soapy drama. And for that reason, I can see why many readers love it! But it won’t be making it into the annals of my favourites. Will I continue the series on audio if I’m stuck for an audiobook? Probably. I don’t know what it’d be like to read this rather than listen to it, but I imagine I’d have been quite a lot more frustrated. Because whilst I say there’s not a lot of scene setting, I suppose that’s not strictly what I mean. It isn’t atmospheric; we don’t get a sense of daily life or small moments, but we do get a lot of description. At one point I was listening to about two hours of a boy setting a fire and I was thinking… I could do with a little less detail here. So yes, if I had been reading this I might have lost my patience with it rather more quickly. But that is why it works so well on audio; when my attention wavered, it didn’t matter all that much. I could still more or less follow the story.

Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury

You may remember I read Dandelion Wine over summer, and this much more famous novel is nominally set in the same place, the fictional Green Town, Illinois. I assume that such a thing as a ‘Halloween novel’ exists and if it does, this is the progenitor of such a novel. It follows two boys who attend a mysterious carnival that turns up on the edges of town a few days before Halloween. They quickly cause enough trouble so as to be pursued by the petrifying figure of Mr. Dark, who wants to trap them inside the carnival forever.

One thing I love about Bradbury’s prose is that the man just goes for it. This is such pulpy, purply prose that at times it becomes quite glorious. I don’t think I’ve written down so many quotes from a single book in months, maybe years. Sometimes the sentence just absolutely works, especially in a horror context ("Waiting, his flesh took paleness from his bones”), and sometimes it’s completely batshit (while a character walks off into the distance; "Somewhere a vast animal made water. Ammonia made the wind turn ancient as it passed”). But at least he is taking risks, he hazards something, he really truly cares about what he’s writing and you can tell. It is a soothing antidote to the abject dullness of much contemporary prose styling, at least that which receives the kind of readership that Something Wicked has received over the years. Because it is also not particularly beautiful or poetic in the way you might think of ‘poetic writing’. It doesn’t seek to create soft reflective images, but rather vivid splashy ones. I like it, I admire the gumption. I want to read more.

But this was nowhere near as successful as Dandelion Wine for me. There are countless reasons to be honest, but I think a major one is that it is very one note. The wonder of DW was that Bradbury was combining different modes and genres into one piece; it was the quiet coming-of-age parts that really heightened the strangeness of the horror or speculative elements. Here we don’t get that quiet, and so we don’t get the contrast or the light and shade. Instead the hysteria of it goes up and up and up, with little release and not enough characterisation or plot line to carry it.

I wouldn’t read it again, but I am glad to have read it, so make of that what you will. I think it’s worth a try because some folks just get on with the style and atmosphere and it carries them through (though obviously it really should be a seasonal read). But within our book club it was not overly popular. It just doesn’t have enough story to sustain you over its 250 pages.

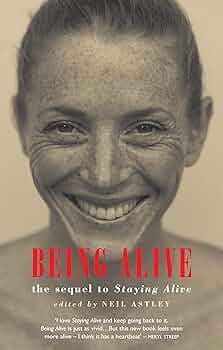

Being Alive ed. by Neil Ashley

I read this poetry anthology slowly over the space of about eighteen months, and it did exactly what I wanted it to do which was give me a long list of poets whose collections I will now seek out. It’s part of a larger series edited by Ashley that highlights contemporary poets writing on all sorts of subjects for an intended audience that is largely unfamiliar with poetry. Ashley clearly wants us to see how poetry should be read and consumed as part of daily life, and need not be restricted only to those who know ‘how poems work’ or ‘how to read poems’. Not just to the snobby English lit student, then. In that respect, I think this volume and I assume the others do a fantastic job, making it a potentially great gift for someone who you think could benefit from a little more poetry in their lives. Unsurprisingly it has a rather Western bent to it, so be wary of that. But overall I very much enjoyed!

I can’t mention poetry without briefly mentioning Tasnim, who posted thirty-one days of poems on her Substack over the summer, if you’re looking for yet more collections to dip into. From now on I’d like to make it a habit of reading a collection a month. Currently I’m reading Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha’s latest, Forest of Noise.

With that, I shall leave you! I hope you enjoyed, and stay tuned for the big speculative fiction round up coming to your inboxes very soon. And we shall be back to normal programming now that I’ve finally completed some of these big reading projects.

As the narrator himself says, quoting writer Ricardo Piglia.

We overlapped on the Hachemi and Croft in October. Both really interesting reads!

Excited to keep reading your thoughts on books and beyond ☺️

Ahh I will hear no slander for anything Bradbury 🙃. You are so right that he goes for it, and as someone who struggles with sincerity I thoroughly enjoy his. Great roundup !