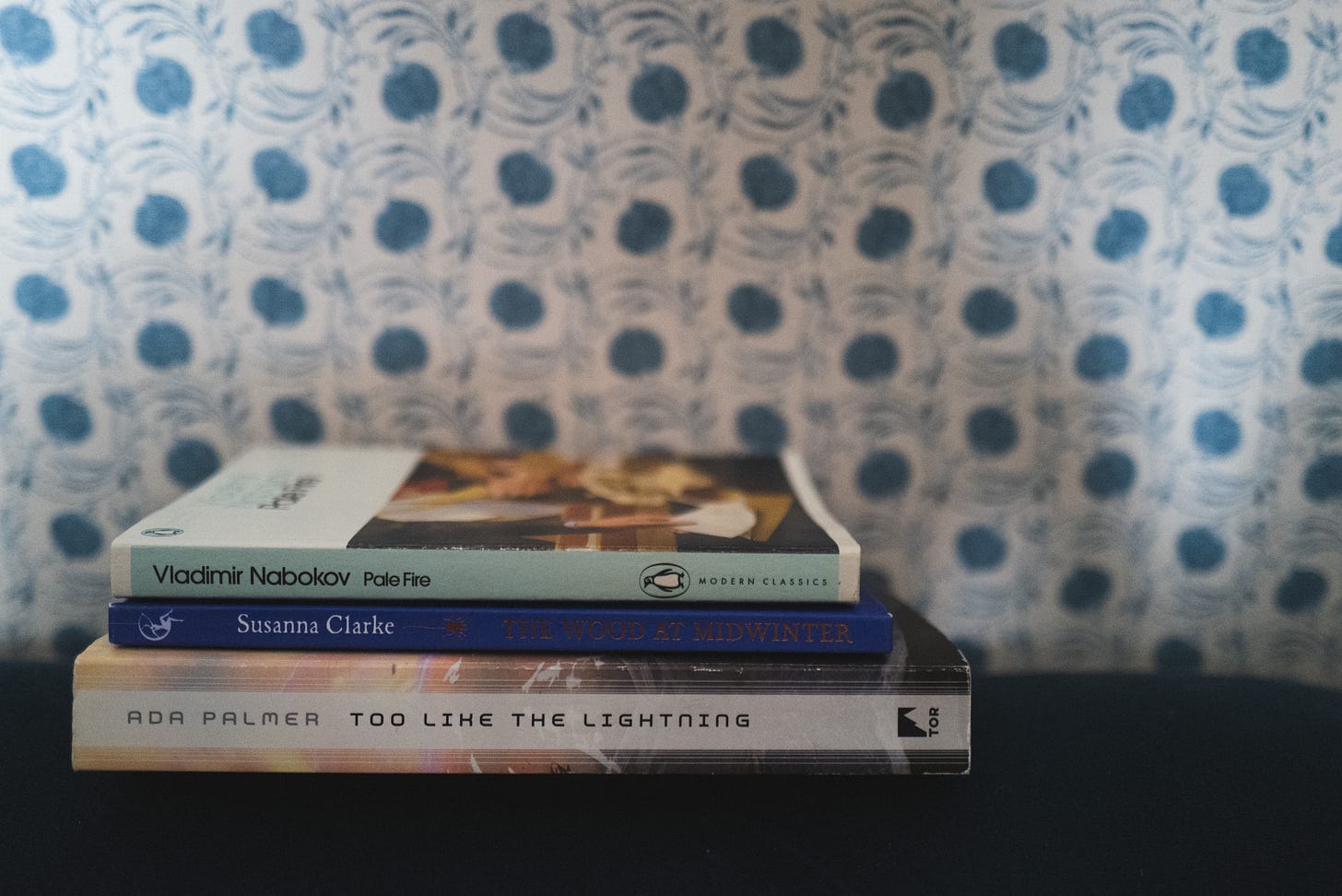

December 2024 Reads

Vladimir Nabokov, Ada Palmer, Mosab Abu Toha, Liz Moore, Noreen Masud

Welcome to one of my monthly wrap-up posts, where I briefly review everything I read! I read widely across many genres, from classics to literary to speculative fiction. With these I’m hoping to shed some light on backlist gems, perhaps push you to read outside your genre comfort zone, and also highlight which new releases are worth your time.

Let’s peer, for a moment, into the distant past that was December 2024, and review the last few books I read in that strange and disconcerting year. Every January I consider not doing this because I am usually later posting it than I would like, partly because I am diametrically opposed to starting one of these before the month is out. It seems I absolutely need to see the reading month in full before I can reflect on it. This is obviously a flawed way to proceed but it’s what I’ve got. Anyway, every year I decide I obviously have to review the books I read in December, seeing as I’ve done it for every other book I read throughout the year. And so here we are. Looking at the words ‘December 2024’ when our minds have all turned towards the fresh page of a new year.

This month held two pretty major disappointments for me, so against all usual protocol I’m going to write about those first and then move into the books I did like. I was very ready to love both Pale Fire and Too Like the Lightning but alas, it was not meant to be. Let’s get into it.

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962)

Oh no, I have a very unpopular opinion here.1 This book should have been an easy favourite for me. I love a pretentious literary puzzle, and I also think Nabokov is a genius. But I found the book to be… lacking.

The book is largely penned by a character called Charles Kinbote. Purportedly, the book is an analysis of a poem (‘Pale Fire’) by a writer named John Shade, who has (duh duh duh) recently died. We have Kinbote’s preface, the poem itself, and then the extensive notes. Only we come to find we are being offered something rather different.

It’s hard to talk about why I didn’t like this book without in some sense ruining it. So if you haven’t read it and do want to go into it fairly blind—which I think is probably the right approach—I give you permission to skim read the rest of this (I’ll avoid major spoilers, though). Partly because although I didn’t enjoy this book that much, I still think it’s worth reading. I wondered whether some of my issues with the book came down to the fact of it being an older version of books I love; without it, perhaps they wouldn’t exist or would look very different. I appreciate Nabokov’s experimentation here, his writing a novel in the form of a poem and analysis to said poem. On a prose level it is light and adept, shifting subtly into different registers and voices (not to mention, the actual poem itself, by turns lyrical and ridiculous). And I think my disappointment registers differently because I had such high expectations. If I read this book from a contemporary author, I might have been pretty impressed; such is the curse of being Nabokov. I’m glad to have read it and would recommend it on all these bases.

But hey, it was a bit of a slog, in ways I didn’t expect. Not because it was dense or because it was annoying flipping back and forth between different parts of the book to follow references. That’s the kind of stuff that really gets me going. I couldn’t help comparing it, in fact, to Possession by A. S. Byatt, which I read in December the previous year, so my seasonal senses were tingling. That, too, features a lot of poetry penned by no less than two different (fictional) Victorian authors, and a number of layered narratives. It is pretentious and English literature-y in all the ways I love. That book seems born out of a real love for this kind of endeavour.

Pale Fire, however, seemed to me to be born out of a desire to mock those academics lining up to analyse it (stung by his experience with readings of Lolita, perhaps?) In my opinion the poem and the notes were just too far apart narratively to make for an interesting reading experience, and actually the storyline itself seems almost straightforward if you follow the clues.2 It doesn’t help that the story we are told in the notes is incredibly tedious,3 or that Kinbote as a character is generally rather unpleasant.4 Don’t get me wrong, many many people have tied the poem and the notes closer together and I read a lot of different theories, but I find myself unable to buy into any of them. I end up feeling like a crazed Kinbote, clawing for meaning where there isn’t any. Or perhaps there are meanings, but they are too many and various—too many possibilities abound due to multiple red herrings that feel like Nabokov is just messing with us, rather than trying to show fundamental instability or hint at some hidden truth. And because this feels to me to be the heart of the novel—analysis is futile—I can’t get invested. There is no truly great story here, no truly great characters. It is an experiment before it is an enjoyable novel. That is fine, but I can’t call it a favourite.

I hate to be that person that puts up their hand in class and says ‘well what’s the point of it analysing this?’ That goes against my very nature. But with this it felt like such an empty endeavour. When I got to the bottom, what would I find? What themes, what heart? It reminded me of reading House of Leaves. Yes, this is all very nice, but you have to be doing it for a reason beyond ‘I’m being experimental’.5 What story do you actually want to tell, and why? Thankfully, because it is Nabokov, there are elements to the book that I think are interesting beyond the puzzle aspect, and if I ever returned to it I’d be focussing on these. In fact, the whole rabbit-hole-of-references aspect I consider a distraction I spent too much time on. I’d follow the theme of mortality, death and haunting. I think this works through the book in an interesting way and possibly has echoes in Nabokov’s other work, too.6

I now prepare for comments telling me I’m wrong.

Too Like the Lightning by Ada Palmer (2016)

I enjoyed Ada Palmer’s introduction to Gene Wolfe’s seminal Book of the New Sun (which I am still halfway through…more on that soon, I hope), and it put her Terra Ignota series firmly on my radar. Not least because it seems to have been heavily influenced by him; a novel which relies on in-depth world-building, mystery, and the accretions of centuries of life.

Well, I was sorely disappointed. In fact, this novel annoyed me more than any novel has done in a while, exacerbated perhaps by a very promising first chapter or two. First of all, we can chuck the Gene Wolfe comparison out the window. Wolfe’s prose is far more sophisticated and subtle than Palmer’s. Maybe I even made the comparison up, I don’t know. Either way, they are not the same.

Honestly, where to start. I don’t know how to go about describing this book because it is almost entirely exposition, with very little plot to speak of. It is styled as a memoir of sorts by Mycroft Canner, living in the year 2454. He is a ‘servicer’, meaning that he has committed a crime of some sort, but in this future world people are not shut away in prisons but made to engage in a sort of permanent (?) worldwide community service. Mycroft—for very tenuous narrative reasons—seems to be ‘in’ with this world’s elite, so we spend most of our time in their quarters, discussing politics and sometimes philosophy. The book starts with the much more interesting potential storyline of a boy called Bridger, who seemingly has magical powers to make things (drawings/toys) come to life. This is quickly abandoned.

Mycroft writes in a faux Eighteenth Century voice apparently because his own time in some ways reflects this period (maybe???) It is a near-utopia, where people don’t live in geographic nation states but rather enormous ‘Hives’, of which there are about seven (all of which you’ll have to become quickly familiar with as the book progresses).7 This is partly made possible by extremely fast flying-car-based transport, which can take you across the world in a matter of minutes. One thing that I disliked about the book was that in spite of all this meticulous world-building of which we must read so much—all the different political statuses of countless individuals and Hives—the idea of what it might mean for humans to no longer have a true geographical home is not explored. In short, I didn’t like the concept as a whole. One need not believe in the concept of nation states to know that humans are tied to and a product of their environment and local geography. Maybe this wasn’t as fashionable of an idea when Palmer penned her first draft, but if you make a world a certain way I need you to think down to the bottom of the idea. Maybe she does it in subsequent books, but I won’t be rushing to read them.

Mostly I didn’t care a jot about these world elites. They were tiresome to read about. The novel needed focus and a smaller, more intimate story. Sure we can have the other stuff, too, I suppose, but we need that to be the core. I thought we would get that with Mycroft, but instead he seems to be flying about attending to the concerns of others. I really had to push myself through large swathes of this novel.

I think the first draft of this was written by 2008, but only published in 2016. This may explain some of the bizarre approach to gender and race. Despite the wholesale abandonment of geography, everyone is described by their continental facial features (yikes!) And in this version of the future, being gendered in language or in person is taboo, everyone is referred to by ‘they/them’. But then Mycroft chooses to reintroduce he/she pronouns back into his own narrative (and then tells us why he’s doing it countless times). It was actually just hard to parse some of it, but it felt gender essentialist at times in an uncomfortable way. Still, I suppose I admire Palmer for trying something rather different at the time of writing, even if it doesn’t exactly match up with current thinking.

Finally, finally at the end of the novel we get a bit of plot. But then we are left with a giant cliffhanger! Over 400 (very large) pages and I have to read the second novel to get even a little satisfaction from the experience!?

And yet, and yet. Some qualifications. I’m not entirely ruling out reading the next book, though as I say I won’t be rushing to do so (perhaps the audiobook could be the way forward). I’m willing to believe that Palmer has matured as a writer since the writing of this first book. There is a lot of potential here, some good ideas, and some real ambition and risk-taking, which I appreciate in any author. More audacity, please. Also, the story is clearly half-finished. Perhaps some of my issues would be less glaring in the context of the entire story. So we shall see. To be continued (perhaps).

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (2024)

Along with the poetry below, this was probably my favourite read of December. This is a nature memoir that documents Masud’s relationship with flat places, which— despite the general public’s imperviousness to their beauty—she finds particularly arresting and magnetic. This particularly in light of her difficult upbringing; first growing up in Pakistan under the control of her authoritative and abusive father, then finding herself curiously numbed to the world upon her arrival in the UK.

I think Masud here manages a wonderful balance that results in something truly resonant and in many ways quite unique. She does not go into huge amounts of detail about her life in Pakistan, using just a few important incidents to give us an impression that still preserves the her privacy and that of her family. And it is not rigorously academic or historical or scientific or literary, even though she touches on all these things in her exploration of flat places and trauma. It seems she knew she couldn’t cover everything in great depth, but she has a knack for pulling out just the thing that will work paragraph to paragraph, chapter to chapter. This is a great and underrated skill, that requires a good ear for narrative voice and rhythm, and I think she has a very distinct one. Although it doesn’t make us, the reader, a voyeur into her trauma, it still feels radically vulnerable, and I was really able to feel her relationship to flat places; the writing is as incisive as it is poetic. Again, no mean feat for a writer describing a landscape, particularly such a featureless one. Overall, it is a very accomplished, confident work, and one that I will continue to think about. I hope she writes more, but if not, I won’t look at a flat place the same again.

Forest of Noise by Mosab Abu Toha (2024)

An utterly devastating poetry collection. Toha is a Palestinian poet who fled Gaza with his family in November 2023. The poems in this collection give a sense of what it is like to live as a Gazan, both before and during the current Israeli onslaught. He slips easily between different tones and registers across the poems, sometimes slow, reflective and beautiful, sometimes filled with rage, sometimes with the cold, empty void of despair. And some of these poems are incredibly raw. This one I can’t stop thinking about. An unthinkable thing that is yet a daily reality in Gaza.

For a Moment

Her small body rides in my arms as I run to the hospital. There is no electricity and the inner hallways are a forest lined with cots. The girl I carry is dead, I know that. The pressure of the explosion tore apart her thin veins. I know she is dead, but everyone who sees us runs after us. You are alive for a moment, when living people run after you.

At times Toha reinterprets poems and forms of poems by famous American poets: Walt Whitman, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Kaufman. We become aware, suddenly, that he is writing all this in English, his second language. He was friends with Refaat Alareer, who also taught and championed English literature in Gaza. Toha escaped with his life where Alareer did not. Toha daily posts on his Instagram terrifying updates, all in English so that we may see and know. At the very least, as lovers of English literature and poetry and art, we can lend our eyes and our ears to Toha and writers like him.

The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke (2024)

This story is so brief it is difficult to review but as it came packaged in book form, I will attempt it. I think I read this at just the right moment (though I wish it had been before Christmas rather than after). It was late at night and I was maybe half asleep already and I read it quietly, peacefully, for about twenty minutes (it really is that short). Quiet and peaceful reading was not something I got a lot of over the holiday period so it was quite lovely, and I was able to capture just that little bit of fairytale magic from it. I probably won’t think about it for a long time, but I’d consider reading this aloud to my daughter at Christmas next year. If I’d paid almost ten British pounds for it, though, I might have been more disappointed.

I actually really liked Clarke’s little note afterwards, particularly regarding a Borges story that I read last year and its relationship to Piranesi. Just some trivia for me to store away in my brain. It was almost worth a read just for that, from the rather reclusive Clarke.

The God of the Woods by Liz Moore

I was left a little cold by this one, the book of the summer.8 I listened to it and I think that probably exacerbated my problems with it, but overall I wanted more. I read and liked Long Bright River, one of her previous books. It felt like an elevated mystery/thriller; a fairly nuanced approach to the themes—and there being themes—and smooth, reliable prose. Whilst this is approaching what we might think of as a literary thriller, it’s not quite in the literary box for me (the essay where I define what I think of as literary is long overdue). I’d forgotten the full extent of my last experience, and considering this one was billed as a ‘literary thriller’, I think my expectations for this were probably a touch too high. As it was, it felt a bit lacking.

We switch between various different perspectives across two timelines. The Van Laar family run a summer camp on their sprawling Adirondacks estate. In 1975, they finally permit their own daughter Barbara Van Laar to attend, where she quickly falls in with the resident outcast and gets into mischief. But she then goes missing. The tragedy is compounded by the fact that Barbara’s brother, Bear, also went missing on the grounds fourteen years ago. What secrets are the Van Laar family keeping?

Two issues with this one. First, whilst we get a lot of character work here across the different perspectives, quite a lot of it feels extraneous to the actual story. I could enjoy the characterisation in and of itself, of course, and some of it I did, but for a book to be truly great everything needs to be there for a reason. In this one it felt like Moore had said to herself that we should know more about these characters to achieve a more elevated style… but why? How does it serve the themes or plot? Barbara’s camp friend, Tracy, for example. Why do we need to learn about her home life, her insecurities? Sure, it makes her feel more ‘real’, but does it really serve the story being told? Perhaps the mini stories inside the larger story just needed to be more engaging. But it begins to feel like padding, no matter how nicely it’s written, and leaves loose threads. Switching back and forth between perspectives also added to the sense of narrative superficiality. The tension was in danger of being lost, and very little was advanced with each chapter beyond some character exposition.

The central problem is that the story itself feels half baked (hence all the dallying with the characters, perhaps). By the time we got to the reveals I was disappointed. The final one even seems a little silly. This is always a risk with mysteries, and it’s extremely hard to please everyone, so that’s where the other elements come in to support. But the combination of difficulties in both the story and its telling meant it just didn’t quite cohere for me. I didn’t really connect.

That doesn’t mean I had a horrible time with it. I can see why lots of people really enjoyed it. I think I just went in with my expectations too high. I suppose I wanted more time in nature, too. Less character, more atmosphere. More outside stuff happening, not just flashbacks and interiority. Anyway, I’d recommend it as a good holiday read (hence its summer popularity I’m sure!) and maybe as a good one for people moving from reading genre fiction to a more literary mode. It’s partway there.

Thanks for reading today! My favourite books of 2024 will follow tomorrow.

Dare I ask for your Pale Fire opinions?

Well, at least in the grand scheme. But we read this for book club and actually pretty much all of us were more or less on the same page about this one. This also meant I got to have some fantastic (occasionally ranty) conversations about it.

SPOILER: Who cares if Charles Kinbote is in fact Botkin??? We don’t know Botkin? What difference does it make!?

I’ll be happy never to see the word Zembla again. If this story had been better, I think I’d have enjoyed the novel a lot more. Its reveal could have been ‘the point’.

The problem of Lolita is that Humbert Humbert’s narrative voice is somehow attractive or charismatic to the reader, even though he is loathsome paedophile. Would I have felt differently about this novel if Kinbote had been allowed to embody a more engaging voice?

I give Nabokov more leeway on this than Danielewski. He earned it.

SPOILER: More interesting than taking this theme and claiming that it’s evidence John Shade’s ghost wrote the poem through Kinbote after his death…

SPOILER: The reveal of this book seems to be that this is not a utopia, which… yeah. We can see that from page one.

Don’t mind me, just reading it six or so months late in the depths of winter.

I felt similar about god of the woods, I also did audible and I wondered if I was just missing the point and what made it so popular.

I really enjoyed your A Flat Place review - one I have been intending to read for a long time. I really loved this line; 'Although it doesn’t make us, the reader, a voyeur into her trauma, it still feels radically vulnerable, and I was really able to feel her relationship to flat places'. It makes me more excited to feel her relationship to flat places - (which in of itself is so poetic. I have been impressed by the concept of the novel from the moment I heard about it) It is such a delicate act of write about trauma and walk that line of balance between sharing some, but not all. I love to hear how masterfully she navigated it!

Also interested in Forest Of Noise (I don't want the/my discussion of Palestinian lit to fall off now the ceasefire has been reached) and enjoyed your God Of The Woods review. For any book that is feverishly popular in the discourse, I always feel like the expectations are never met. I often avoid those books for this exact reason so made me smile that you had a somewhat similar experience.

I very much look forward to your 2024 favourites !!