May 2025 Reading Review

Sigrid Nunez, Tove Ditlevsen, Anuk Arudpragasam, Angharad Price, Nicola Griffith, Isabella Hammad

This post is too long for email, so do switch over to your browser or the app to read the whole thing.

Welcome to one of my reading round-up posts, where I take stock and review everything I read over the course of the last month! I read widely across many genres, with a particular focus on literary and speculative fiction alongside some classics (and the occasional dose of nonfiction, too). With these I’m hoping to shed some light on backlist gems, perhaps push you to read outside your genre comfort zone, and also highlight which new releases are worth your time.

Writing these reviews, I’m struck by how many great books I read in May. I started the month with a book I think should be considered a contemporary American classic, Sigrid Nunez’s The Last of Her Kind, and then continued to have fun in New York with Joanna Rakoff’s memoir My Salinger Year. In the second half of the month I read a spate of deeply moving novels, including Han Kang’s We Do Not Part, Anuk Arudpragasam’s A Passage North, and The Life of Rebecca Jones by Angharad Price, which confirmed for me that reading great books is a spiritual activity as much as anything else. Much to recommend—read on!

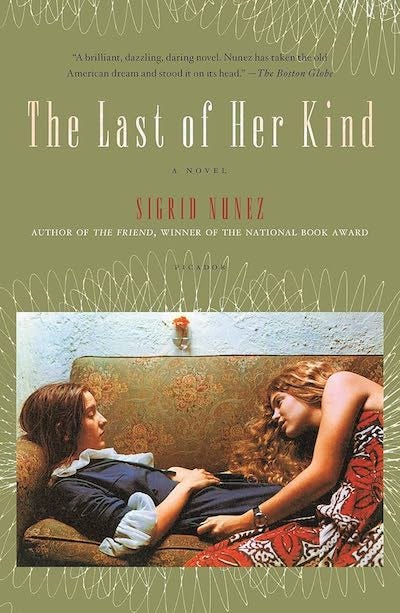

The Last of Her Kind by Sigrid Nunez (2006)

A week after Georgette George arrives at Barnard College in the late sixties, her roommate Ann Drayton blithely reveals that she’d asked to be “paired with a girl from a world as different as possible from her own.” Ann—a privileged young woman from a well-to-do Southern family—is a little disappointed because Georgette isn’t… well, Black. And thus begins Sigrid Nunez’ 2006 novel The Last of Her Kind, a novel which, amongst other things, explores the ideological extremes of the late sixties and early seventies.

In her own mind, Ann means well. She is a belligerent activist, for whom even the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) is fundamentally flawed, driven as it is by privileged young people like herself. Throughout the novel, she works consistently against her own interests, even when the effect seems only to maintain an ideological purity rather than to instigate any material change in the lives of the marginalised. It becomes clear that much of Ann’s fire comes from a place of deep shame and self-hatred, but in repudiating wholesale all she came from, she ends up fetishising the poor and oppressed classes in ways that are sometimes uncomfortable, at other times downright harmful. I don’t know how this read in 2006, but this kind of person is rather familiar to any of us who have followed certain strains of online activism from the past fifteen years or so.

Is Ann the last of her kind, then? Not really. Much of the novel seems to be Nunez trying to figure out Ann and people like her (she makes reference to similar historical figures, like Simone Weil and St Teresa de Ávila). Does it matter if your activism comes from a place of shame? Is it less effective, and why? Can anyone be radically honest with themselves in the way Ann seems to be, or is there always something hidden, lurking, in one’s motivations? Is ideological purity important, or can it be counterproductive? How can a privileged person meaningfully engage in this kind of politics? What happens when someone is—in a broad sense—right about something, and yet their ideas also seem to feed into a destructive mental health problem? Ann isn’t delusional, exactly, but neither does she seem entirely healthy. And if she does make some small difference in the world, where might we find it?

One can imagine this kind of novel being pretty ham-fisted in its attempt to carefully peel back all these layers. But Nunez avoids many of the pitfalls by picking the perfect narrator. Whilst Georgette doesn’t perfectly fulfil Ann’s roommate criteria, she’s still quite different from Ann in that she is from a working-class background and has had a difficult childhood. She’s never really interested in politics, and instead pursues a fairly comfortable life in New York. Still, Georgette is drawn back to Ann and thoughts of Ann, even as the two women grow estranged after college.

For some readers Georgette feels under-characterised and strangely blank. She’s our narrator, and yet we find things out about her almost incidentally, and many of the major events of her life are quickly glossed over. Yet I find her to be the perfect vehicle for this story. She is empathetic towards Ann (especially when she does something extremely drastic about midway through the novel), and her empathy allows us to maintain that careful, almost impossible, balance; we don’t have to agree with Ann, but Georgette can (and Nunez knows just when to introduce a dissenting voice). Too much characterisation of Georgette would get in the way; we might have to judge her more harshly for her continued identification with Ann, for example. This, to me, is the perfect use of a first-person narrator.

In many ways this feels like a very literary book, both in content (via Georgette’s succession of jobs in New York), and in style. Our narrator is more of a literary character than she is a supposedly psychologically real person (and is almost certainly a riff off Nick Carraway of The Great Gatsby); she embodies what it means to be the lens and voice of a novel, not of life.

This dynamic between Ann and Georgette is the driving force in the book, but Nunez covers so much here in ways that make for a wholly satisfying reading experience. She paints a picture not just of the protest generation, but also of the simultaneous advent of the hippie and free love movement through Georgette’s sister’s experiences (a perfect foil to Ann). Nunez is adept at bringing this particular period to life (just look at all the Goodreads reviews from those who were young during the 60s and 70s). As I mentioned, it’s also a nostalgic trip down memory lane to literary New York, complete with criticism of criticism. And if that weren’t enough, she also includes a variety of other materials, including newspaper articles, interviews, courtroom transcripts. Georgette herself even seamlessly moves between different registers throughout that kept the narrative style feeling fresh.

This book is eminently readable. Too meandering for some, perhaps, but I found it compelling throughout, with all this literary sleight of hand. Nunez does not try to impress at a sentence level; instead she layers styles, content and themes in ways that elevate the whole. It is a nuanced, never simple examination of Ann and “her kind”, yes, but it’s also just a great story, well told. Can we ask for much more than that?

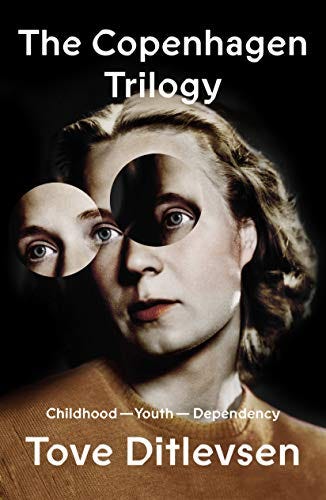

The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen trans. by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman (1967; 1971)

In 1967 renowned Danish author Tove Ditlevsen published the first two volumes of what would become a trilogy of remarkable memoirs. The first two—Childhood and Youth—cover her early life growing up in a working-class neighbourhood in Copenhagen as an aspiring poet (it seems she was born this way), and entering the workplace in a string of jobs she likes more, or less. The final volume, Dependency, details her four marriages and a five-year period of life-threatening addiction to demerol and methadone. All this in less than a hundred and fifty pages! Though to be fair, it is the longest of the three.

These books are spare, then, in style, but with a latent energy and urgency. Ditlevsen speaks to us with a startling frankness, detailing all the scenes—from the most nightmarish to the most euphoric—in much the same tone. She cares little for our judgement and metes out none of her own upon the players of her life, including herself. Sometimes she does depart from the elegant but more workaday prose into some soaring poetic conceit, including the rightfully notorious and marvellous: “Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin, and you can’t get out of it on your own.”

Many reviewers spend a lot of time on Dependency, for obvious reasons, but I find myself drawn to Childhood, where her writing truly sings. Was it the bigger temporal disjunct (and the fact that I believe the main stars of this volume—her parents—had passed away by the time of its writing) that allowed her more freedom, a more productive mix of healthy fictionalisation and memoir material? Even so, the trilogy as a whole is an impressive if sobering work, documenting the life of a woman who, even while ostensibly living her dream making good money as a writer, is plagued by the demands of wifehood, a string of unsuccessful marriages, and addiction. Sadly, the ending is not a happy one, though within the bounds of Dependency, at least, there is a reprieve of sorts by the end.

I recommend this to anyone who enjoys autofiction, or stories of writerly women. Autofiction is not a genre I automatically get on with and sometimes actively avoid, but Ditlevsen knows well that one must tell an effective story just as much as you must lay out the detail of your own life, and there are few stories more compelling than her own.

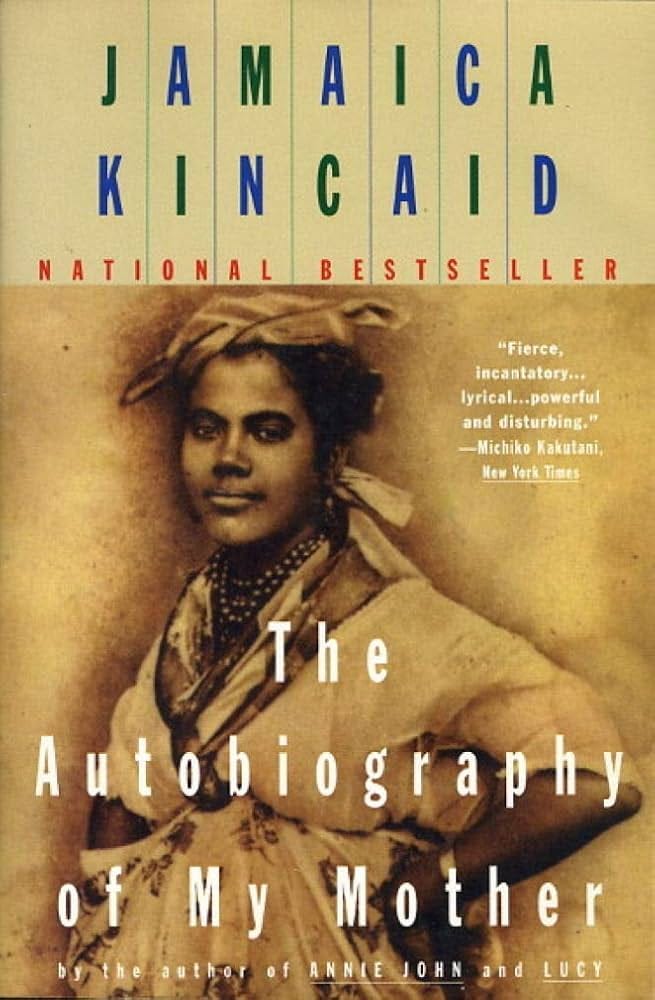

The Autobiography of My Mother by Jamaica Kincaid (1996)

I covered this in my How to Read and Analyse a Novel course in May, but as it’s been so long since I first reviewed it, I thought it deserved a brief mention here, too.

Xuela is born and raised on Dominica, a Caribbean island that was only granted full independence from the British after hundreds of years of colonial rule in 1978. Over the course of the novel, Xuela tells us about her life, and how she grew up in what she felt to be a loveless world. She has a mixed-race father who identifies with the British and repudiates his African ancestry, and a Carib mother who died when she was born, and so her life is shaped by the legacies of colonialism. This legacy seeps into everything, replacing love with mistrust and self-hatred in her social circle. As an act of rebellion, Xuela decides to pour love into herself, though this doesn’t come without sacrifices of her own.

Kincaid’s prose is elliptical, iterative, dense with meaning and lyrical in mode; through it, she brings the inimitable Xuela to life. As the novel goes on, it begins to abandon even those initial concessions to scene and specificity and moves into an even more reflective mode. Whilst distinct scenes and concrete detail are usually very important to me, Kincaid produces some of those rare exceptions. First of all, it all serves to further characterise Xuela, who I take to be a woman who is extremely clear-sighted on the deep and lasting effects of so many decades of colonial rule, but who is also a deeply traumatised and vulnerable character, having no warm parental figure on which to rely. Her story therefore feels both general and specific in ways that only a great novel can achieve.

It also all serves her themes and purpose with the book, in a manner that other reflective, dreamy narratives do not. This makes it a sometimes difficult read, but one whose effect continues to grow until the very last lines. It is a novel that has stayed with me since I first read it almost ten years ago, and it’s been a good reminder to return to some of Kincaid’s other work very soon.

You can click here to read a more in-depth analysis.

My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff (2014)

This memoir details Rakoff’s year-long experience at an esteemed literary agency in New York in the mid-90s. Her boss is staunchly against all those newfangled inventions like computers and emails, meaning that the office serves as one of the last enclaves of a pre-digital publishing world. It’s lit by low lamps and the floor is lushly carpeted; the assistants spend their days listening to their boss’s voices murmuring through dictaphones as they type up correspondence on a typewriter.

The supposed premise of the memoir is that Rakoff spends a rather large chunk of her time reading and replying to fan mail for J. D. Salinger, one of the agency’s clients. Whilst this certainly plays a role in the book, overall it’s more of a nostalgic look back at this vanished world. One in which troops of young people pour into the city from their outlying neighbourhoods, manuscripts in hand, hoping today’s the day they’ll attract their boss’s attention and rise in the ranks. One in which getting a foot in the door might not be entirely effortless, but feels just that bit more possible. One in which people could visualise a long and relatively remunerative career in the publishing world, if they kept working hard and if they liked books enough. One in which people would stay so long in a certain agency or publishing house that decades-long relationships between writers, agents and editors would be relatively normal. Ah, the good old days.

This is that old dream of literary New York, where the spruced-up secretary jobs (“editorial assistants”) involve mostly menial work and yet retain some of the glamour of the institution. And alongside her experiences at work, we see Rakoff deal with deteriorating college friendships and a rather unsavoury Marxist boyfriend.

All in all, this was a fun, light read. Rakoff arranges the narrative well to maintain tension and keep you reading, and I enjoyed immersing myself in this world for a brief time. I recommend it to anyone for whom the above sounds rather inviting.

A final note: I read this in the Slightly Foxed edition, which they sent me a few months ago. They are pocket hardback reissues of classic memoirs, and they’re lovely! I wanted to keep reading this book partly because holding it was just such a treat, and this is coming from someone who usually hates hardbacks (they are small and light but the quality still feels wonderful). They also produce a quarterly magazine. You can buy their books individually or you can subscribe and receive them throughout the year.

We Do Not Part by Han Kang (2021; 2025) trans. from Korean by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris

I’ve read both The Vegetarian and The White Book, and while I liked both I wasn’t bowled over by them, nor do I remember much about either a number of years on. Whilst I was looking forward to reading it—we picked it as our quarterly new release choice over in book club—I can’t say I was especially excited about it.

Readers, I loved this book. I’m actually planning to reread it this month (here’s hoping—reading plans very quickly go out of the window around here). But how on earth to go about describing it?

Our narrator Kyungha is at a low ebb. She feels alone, lost. One morning she receives a message from her friend Inseon to come to the hospital; when she gets there, she finds that Inseon has had a woodworking accident and has to remain there for a few days whilst she recovers. She’d like Kyungha to go to her remote house on the island of Jeju to look after her bird, who will die if she is not given regular food and water.

How to describe the tone of this novel? It is muted, haunted; poetic and yet precise. Much of the novel takes place under the weight of an ever-falling snow. And though it’s a novel that requires some close attention from the reader to follow its various flashbacks a conversations, there are also many vivid, atmospheric scenes that stand out in the mind’s eye. This keeps the book grounded, preventing it from floating off entirely into indistinction. In fact, there is a delicate balance at work throughout, so that each mode—the concrete and the dreamlike—perfectly sets off the other.

As Kyungha explores her friend’s home, the story of Inseon’s family is slowly uncovered, particularly her parents’ experiences with the massacres that took place on Jeju in 1948–9, which left at least 30,000 civilians dead. This book is a testament to remembering in spite of everything, in spite of silencing. An apt message for our times.

We will be discussing this next month over in book club, and I think this novel will so reward extended discussion. There is so much to dig into, and that—to me—is the sign of a great book. Suffice to say I will be reading more of her work now—I’ve heard great things about Human Acts, so that’s where I’ll be turning my attention next (a novel which I actually think has some particular relationship with this one).

The Life of Rebecca Jones by Angharad Price, trans. from Welsh by Lloyd Jones (2002)

Rebecca Jones is born and raised in the Welsh valley of Maesglasau in the early twentieth century. We meet her at the end of her long life, as she narrates her own experiences, as well as those of her parents and her three brothers born blind (and one who was not). This is a quiet, slim novel that describes rural life in a place which retains the Welsh language and Welsh heritage against forever-encroaching forces of English assimilation.

It’s hard to believe that this is a work of fiction (it is technically based on the author’s family, though—there are even some photographs). Price truly embodies Jones’s voice, painting life here in vivid tones, so much so that though major events pass us by in a matter of passages, even sentences, we get the feel of something with great depth. It is tender, clear-sighted, smart. Interspersed among the chapters are interludes describing the geology of the valley, or its streams, or what happens atop the mountains that surround it. This lends the novel an epic, timeless quality, though one is ever aware that the peace and tranquility of this remote valley cannot be maintained forever.

I can only imagine that this book sings even more in the original Welsh. Still, Lloyd Jones’ effort is a valiant one, and to my inexpert eye it seems to retain some of the musical quality of the Welsh language. Highly recommended to all who like their quiet, reflective novels—I don’t think you’ll read another quite like this.

A Passage North by Anuk Arudpragasam (2021)

We meet Krishan as he comes home from work; he talks briefly to his grandmother, though he almost immediately wants to extricate himself from her inane conversation so that he can mull over an email he just received from an ex-girlfriend. Then he gets a call—his grandmother’s former carer, Rani, has died. Her funeral will be held in the northeast of Sri Lanka in a few days, and he’s asked to attend. Over the next few days, as Krishan journeys north, he reflects on many things: his grandmother’s struggles with old age; his experiences in love with someone fundamentally unreachable; and what he knows of Rani’s life, marked as it is by losing two sons to the Sri Lankan Civil War.

I reread this novel for book club this month (I first reviewed it here), and if anything I was even more impressed with it this time around. We shall see if I’m proved right, but I mark Arudpragasam out for greatness. He manages several almost impossible things here.

First, he writes in a stream-of-consciousness–adjacent style. Even by its best practitioners, I am usually pretty sceptical of stream-of-consciousness. Though perhaps the ‘adjacent’ bit is what makes it work here (third-person, slightly more sense of time and structure, flashback scenes that provide interest). His sentences are long and rhythmic, and they draw you deep into the book. You might find it hard to put down once you enter its flow.

The book manages to be profound without feeling like it’s trying too hard. One gets the sense Arudpragasam has actually thought all his Proust-style observational stuff through (perhaps this seems like a low bar, but it really isn’t—the thinking part seems to be a lost art). And so it is actually profound, actually thought-provoking. It’s unaccountably beautiful, in fact. There were countless passages I could’ve chosen, but here is one example that I’ll probably never stop thinking about:

He continued gazing at her, at the severity of her profile and the vulnerability of her gaze, and it was as though he could feel the sight of her penetrating his eyes in real time, burning itself delicately into the film of his retinas, forming an image that would remain imprinted in the back of his eyes like a shadow or like tracing paper over everything he saw subsequently. And maybe it was for this reason, it had occurred to him at that moment, that eyesight weakened with the passing of the years, not because of old age or disease, not because of the deterioration of the cornea or the lenses or the finely tuned muscles that controlled them but because, rather, of the accumulation of a few such images over the course of one’s brief sojourn on earth, images of great beauty that pierced the eyes and superimposed themselves over everything one saw afterward, making it harder over time to see and pay attention to the outside world, though perhaps, it occurred to him now, four years later in the country of his birth, walking at the back of the procession bearing Rani’s body for cremation, Rani who’d seen so much that she had never been able to forget, perhaps he’d been naïve back then, perhaps it was not just images of beauty that clouded one’s vision over time but images of violence too, those moments of violence that for some people were just as much a part of life as the moments of beauty, both kinds of image appearing when we least expected it and both continuing to haunt us thereafter, both of which marked and branded us, limiting how far we were subsequently able to see. (pp. 260–261)

You can see how the sentences just run on and on, you can’t stop reading them. It’s one of those books that, if it works for you, will likely stick with you, as it has for me. A novel I will continue to return to.

The Parisian by Isabella Hammad (2019)

Midhat Kamal, a young Palestinian man, is sent by his father to study medicine in Paris in 1914 to avoid conscription. So begins Isabella Hammad’s ambitious debut, which spans several decades, characters and settings. Midhat’s time in Paris is formative, and his abrupt departure—prompted by a miscommunication in love—haunts him for the rest of his life. He’s never quite able to get over the woman he falls for there, or the romance of Paris itself. Whilst he makes a life for himself of sorts in British-occupied Palestine, he is never again satisfied.

Enter Ghost is one of my favourite novels released in the last few years, so my expectations were high. Alas, this novel is just not quite there. Right from the start the plotting felt a little baggy and unfocussed, and in a sprawling novel like this one, that can be a major problem. There were certainly things I admired; I liked Hammad’s commitment to writing a proper twentieth-century novel here. Occasionally she really nailed the world-building, or narrative voice, or added depth with an extended conceit or metaphor. All the signs of a great novelist are here—it’s just a debut! And that’s okay.

Its biggest problem is Midhat. I’m not someone who typically complains of a character being flat or vague—I think these things can serve a purpose. But in a character-driven book of almost six hundred pages, having a bit of a blank for a protagonist was always going to be an issue. There were many of the parts of the novel that I felt Hammad really lived what she wrote (something very evident in Enter Ghost), but many of the Midhat sections felt unlived-in. Like a sketch of him had been made and then not filled in further.

One of the best things about it is its depiction of Palestinian life in the early twentieth century. A world now largely lost.

This is a novel for the Hammad completists among us—those of us who just loved Enter Ghost that much and want to follow her whole career. But for its own sake, I’m not sure I could confidently recommend it. Don’t just listen to me, though—there are many who loved this novel, and found its meandering ways captivating. But it was always going to pale in comparison to Enter Ghost, especially as I’d just reread it, so my expectations almost definitely interfered with my perspective.

Spear by Nicola Griffith (2022)

Griffith was in the middle of writing Menewood (which I reviewed back in February) when she was asked to contribute a queer-coded ‘Matter of Britain’ (Arthurian) tale to a new anthology. Though reluctant to take time off writing Menewood, she was struck with inspiration, and soon the short story had expanded to a short novel of around 180 pages in length.

She recasts the legend of Perceval (Peretur, here), gender-switching the character—who famously grows up in the wilds and becomes one of the Knights of the Round Table—and adding a few further twists of her own. Griffith takes a while to warm up; she’s an . . . abundant writer (remember that though this is comparatively short, it began as a short story . . .) and she probably took a touch too long for me to get to the action. She doesn’t have the hundreds of pages of the Hild series to work with here, and so the pacing felt a bit off. When we did get to that second part, though, it was a lot of fun. I’d always wished there was a little more magic in Hild, and I get that here. In general, it reads extremely similarly to Hild/Menewood (perhaps a little too similar?), so if you like those, you’ll like this. I’d still recommend starting with Hild though to read her masterpiece.

I must note that I read this in a really scatterbrained fashion, so I’d need to reread it to give a truer assessment, but those are my general thoughts. I am now keen to read more ‘Matter of Britain’/Arthurian stuff, though, so if you have recommendations, do let me know. I’m thinking T. H. White? He was always hovering around the edges of my childhood I feel, and yet I never quite got there.

Why Fish Don’t Exist by Lulu Miller (2020)

Radiolab’s Lulu Miller is dogged by a persistent and dangerous depression. Unable to reckon with the world as the chaotic place it is—a world that says ‘you don’t matter’—she decides to try and seek answers in the life of David Starr Jordan, a man who seemed to resist that chaos in all his doings.

Jordan was a famous taxonomist and ichthyologist living in the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries. He achieved enormous success in his lifetime, not only identifying and naming thousands of fish, many for the first time, but also serving as the founding president of Stanford University. When an earthquake destroyed his life’s work in 1906, he just started again. It is this anecdote that sparks Miller’s imagination: how do you continue in the face of disaster?

The thing is, Jordan was also a pretty shady guy. He was a staunch eugenicist and may have committed a murder (maybe). Nonetheless Miller wrestles some sort of lesson from his life; she finds the commitment and wherewithal to go on (or at least to keep “the gun” at bay) and keep trying no matter what.

This is probably not my preferred style of book. You can certainly feel the influence of radio and podcasting on her writing, which is mostly quite interesting (where, exactly, does this feel come from?), but I admit that the light, comedic tone is not generally something I connect with. I enjoyed it in the moment, but probably won’t dwell on this book for a long time. It’s a little too loosey goosey with the facts in the name of a good story in ways I don’t particularly like in science-based nonfiction, and the link between Miller and Jordan is a probably too tenuous for my liking. I can see a lot of people enjoying this book, though. It’s fairly light and breezy despite the subject matter, and life-affirming, too. Still, I’m not surprised that it wasn’t shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, from whose 2025 longlist I picked the recommendation up from.

How to Read and Analyse a Novel Books

As you probably already know, I’ve been running a course on here called How to Read and Analyse a Novel. This is now finished (!), but the posts will stay live so you can take it in your own time (start here if you’re new). Of course I covered The Autobiography of My Mother above as it’s been a long time since I reviewed it, but the rest I have touched on in the not-so-distant past. So here are the other books we covered this month and their respective posts! (I love these books but can’t possibly write more on them to save my own sanity and your inbox. My original reviews follow each link.)

The City and the City by China Mieville original review

The Shipping News by Annie Proulx original review

And with that, I shall leave you! Make sure you subscribe if you want to read next month’s reviews, which will include The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell, and Beware of Pity by Stefan Zweig.

Thanks for review. Really interesting selection of books. I have read Nunez's What are you Going Through and enjoyed it although I thought the storyline rambled a bit. I will look out for the one you mention here. I loved the Copenhagen Trilogy from Childhood to Dependency. Thought it was devastating the way she progressed into addiction whilst trying to carve out a writing career and identity. I have recently read Greek Lessons by Kang and enjoyed it but wasn't blown away by it. This new book is getting very good reviews including from a serious reader in my Bookclub. As it's based on historical events I want to read it soon. Toddling off to our local library to get a copy.....

Wow what a good month! This May reads contrasts so starkly with mine in a way that gives me hope (I always find after a bad reading month I loose faith a little bit in reading, but it always comes back!) It was nice to read so much praise about so many books! Super interested in reading The Last of Her Kind - I recently acquired the my first Nunez in My Friend.

I would echo your love for Childhood specifically in the trilogy - I read it last year and was so taken with the whole trilogy, but felt Childhood was absolutely the strongest. Imo Youth and Dependency are carried by the setting up of herself, her desires and her family that she does in Childhood. The way she writes about how she perceived things as a child still sits with me today - so bold and introspective at such a young age it is literally remarkable. It was devastating in so many ways to watch that fade away as the trilogy continued.

Adding The Autobiography Of My Mother to the tbr! Ever since I read and loved Annie I want more Kincaid BADLY. She is so good.

& I am very intrigued by We Do Not Part! I have read The Vegetarian but honestly, for reasons I am not entirely sure of, I have never felt massively pulled back to her work. I have a sneaky suspicion it might be because Kang is so often talked about in popular and admirable tones, my subconscious decided to avoid it. Anyway your review has made me seriously reconsider going back and I think I will start with this one!

I read A Passage North a few years ago before I think my obsession w the craft of writing really uncovered itself and I remember not liking it very much. I feel quite compelled to revisit it after your review because I can't help but feel like I missed something... I am getting vibes of right book wrong time perhaps.

And, finally, I am gutted and appreciate your review of The Parisian. I think everything you said makes sense - its her debut, we have read SUCH remarkable work from her more recently that it definitely sets up an expectation for that novel that is perhaps unfair. I think I would go into The Parisian expecting another Enter Ghost in many ways too. I think I will read it one day, but it is good to know I should try and scrub the expectations I have of it rn from my brain and be more open to taking it for what it is, how Hammad used to write, not how she does now!