I think it could be the first time ever that every book I read this month sits more or less on the same longitudinal line of quality (well, at least by my own reckoning). These were all great books that I really enjoyed, all of them with something noteworthy, unique or special. But none without their flaws.

I’ve been talking about it a lot recently so forgive me for saying it yet again, but I’m beginning to like thinking about a book’s flaws more and more, and even liking the flaws themselves. I gave up on star ratings years ago because I found it more and more difficult to parse a whole novel’s complexity down into numbers. But recently it feels like I’m dropping even more of that internal hierarchy. Perhaps it’s taken me a while to shake off the ghost of the star rating. I feel like I’m engaging a lot more with each text as its own thing, and also like I have a much deeper sense of books as the product of a wholly human person. In turn that means I’m not so much searching for a ‘perfect’ book all the time anymore (though it’s nice when you do find a work which you think is nigh on flawless, of course), but more just interested in the ways books overlap, differ, converse. And rather than anything I know intellectually, I’m experiencing this as a feeling. I can feel more the uniqueness of each experience; the total individuality of my mind meeting the author’s and then meeting (more often than not) the members of the book club community’s minds. Isn’t art fascinating and also super weird? And am I getting old and sentimental? Very probably.

Now don’t get me wrong, there are still books I read which I don’t think are great works of literature, and I’m sure I won’t be abandoning my Great/Good/Fine rankings just yet. You need the crappy books to balance out the good, to show you what is good. But these books in particular and how they all came together in June prompted me to think outside these boundaries more than I usually would. I’m sure it’s also partly to do with the fact that I’ve written so much recently about what I think constitutes a good novel. It’s like as soon as I put something like that out in writing, my mind discards it completely, pushes past its boundaries into somewhere new. Thanks a lot, brain! Recalibration of what makes a good novel, of why I read novels, continues.

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

Considering this, I think we’d better start with East of Eden. This book is a convergence for me of a few things; an enjoyable and engrossing reading experience, an acknowledgement that it’s not without some rather major flaws, the sense that these flaws are what make it such a fascinating and discussion-worthy novel and the fact of its legacy and context standing so tall in the literary imagination.

We follow two farming families living in the Salinas Valley in California. One of them is based on Steinbeck’s own maternal line, and the other is a fictional creation that reenacts the two seminal stories of the book of Genesis; Adam and Eve, of course, but more importantly that of Cain and Abel.

Over the course of two meetings book club talked for three and a half hours about this book, so I’m going to have trouble synthesising my thoughts into these few paragraphs, I’m sure. First of all, Steinbeck writes a great sentence. There are some real showstoppers in here. And his nature writing is beautiful, he really captures something of the essence of the Salinas Valley. There is something deeply warm and humane in his writing which is what, I think, makes this book enduringly popular.

He wrote a lot about writing this book (also interesting!), and at one time acknowledged that it was a kind of primer for his sons, to tell them about their family but also to teach them how to be good people (no coincidence that two pairs of brothers form the main axis of the novel). He also commented that he put everything into this. Naturally there are semi-autobiographical details (little John actually appears in the book!), there is philosophy, commentary on America and its history, its culture. And although it is six hundred pages long, it flew by for me.

This book has always been popular with readers, but often less so with critics. A book this weighed down with so many simultaneous objectives (history of the Hamilton family, myth-making for America, trying to work out what makes a person good or bad, biblical allegory to support this) is bound to be chaotic. At the time of its publication, many criticised his broad strokes attitude to the themes of good and evil, the somewhat one-dimensional and monstrous depiction of the main female character Cathy, and the weird use of the first person narration. All of which I think are probably fair. But oh, how interesting these things make the book.

We talked about Cathy for a long time, rescuing her from inhumanity, contextualising her, wondering if there were more nuances (intended or otherwise) within the text. Wondering how a text changes over time, going above and beyond how and why it was originally written. And I found the narration fascinating. I didn’t even know it was based on Steinbeck’s family and so thought he was making really conscious choices with his narrator at first (how does the narrator know such intimate details of both families when they are only descended from one? What will the narrator’s role be in the story, considering we open with a strong sense of their voice?) and then realised partway through that it was a more historical effort. How revealing, of the project Steinbeck is carrying out here. It adds a vulnerability to this text that undermines and yet also highlights its myth-making endeavour. It’s an unusual thing to do, and pushes it away from the social realism Steinbeck is known for.

Good and evil, well, yes, those are big topics. For the most part I think there’s more complexity here than you might otherwise suspect. Not only do we get one set of Cain and Abel brothers but we actually get two, both with their own slight differences from the original story. The main reason for the use of this ancient narrative seems to be asking questions about fatherhood, about nature versus nurture and free will, rather than making a religious point. Additionally, some characters seem to represent multiple biblical figures. And the conclusion of the novel seems to suggest there are no wholly good or bad people (does Cathy complicate this, or is she redeemed, too? What of the seemingly morally flawless Lee, or Sam?)

So yes, it’s a melting pot of so many things. And that makes it pretty fun. By the end, you’ll almost definitely feel something. Needless to say, The Grapes of Wrath is high on my list now. It’s generally considered (by critics, too), to be Steinbeck’s best novel, and I’m so keen to see how it differs from this one. If that same vulnerability exists in it, or whether it is a tauter, slicker novel. We shall see!

That Old Ace in the Hole by Annie Proulx

Another novel that exists as a chaotic mishmash of ideas and stories, perhaps with even less of a through-line, That Old Ace in the Hole was an interesting and up and down reading experience for me. At first I was engrossed, then I lost momentum with it, then it picked up enough that I could steam to the ending which I found pretty moving, actually. But I finished it a bit disappointed considering how much I love Proulx’s other work. Then I went back through my notes and realised I liked more elements of it than I thought I did, and that perhaps there was something I had missed in my rather fragmented reading of it (one of those you should read quickly, if you can). I’d like to return to it at some point to get a better feel for it.

We follow Bob Dollar, a man who’s not really sure what he wants to do with his life. Abandoned by his parents as a child and brought up by his loving but slightly odd uncle, he finds himself accepting a position with Global Pork Rind, scouting for spots in the Texas panhandle to set up hog farms. Naturally these hog farms are very unpopular with the residents, being toxic to local water reserves and air, unethical to the pigs and also immensely smelly. So Bob has to invent some sort of cover story for himself, ingratiate himself with the local community of a town called Woolybucket, and see who might be willing to sell up. This is obviously a job that requires some moral dampening, and yet Bob is depicted sympathetically, naive perhaps to the full implications of his job, sometimes internally conflicted by his deception.

There are some wonderful sections in here, particularly the opening pages delineating Bob’s childhood:

A few months after his parents’ fateful departure Bob had started thinking of his slippery self as a reindeer, and he carried his head carefully to avoid hitting his antlers against cupboards or wall projections. It became an intensely vivid fantasy. He had no idea who he was, as his parents had taken his identity with them to Alaska. The world was on casters, rolling away as he was about to step into it. He knew he had a solitary heart for he had no sense of belonging anywhere. Uncle Tam’s house and shop were way stations where he waited for the meaningful connection, the event or person who would show him who he was. At some point he would metamorphose from a secret reindeer to human being, somehow reconnected with his family.

Who hasn’t sometimes felt so sensitive and at a loss that they’re like a secret reindeer?

Proulx writes with her slight wry humour, she loves her characters but also lightly ribs them throughout. The folks of the panhandle are drawn with warmth and careful writerly attention. There are some vivid scenes, like the one featuring the quilting club he ends up sitting in on, with all the elderly local women sharing stories as they vividly depict the visage of James Dean as Abel in their Cain and Abel themed quilt (East of Eden reference alert! Funnier because James Dean plays the Cain character in the film version).

The novel drifts into various little stories of some of the residents, going back and forth as Bob drives around, hoping to catch a break. You’ll have to keep your eye on the names in this one, because it’s easy to lose track. I got lost a few times. Slowly, slowly, we build to Bob’s redemptive arc. If I had been able to read it in a more condensed way, I think I would have felt the iterative rhythm of its movement a little better. It’s quite beautiful, but something niggled in the back of my mind. There’s no doubt that Proulx romanticises settler and panhandle life in this novel (though she also acknowledges some of its history before the arrival of European immigrants, as well as settler colonialism). There is nuance here, but the overall arc of the story takes us down a particular road. Of course East of Eden does this to some extent too, but being an older novel I’m more lenient with it. I don’t say this to dismiss the whole project of this novel out of hand, but it’s worth being aware of what books are doing to us subconsciously as we read them. At the same time it does exist as a record of sorts of this way of life, and the people that lived there, and it is interesting. I think she spent a lot of time with folks from there, and you can tell.

I’m definitely going to continue to read Proulx’s work, she’s on my ‘to complete’ list. There is a reason she is so beloved in the literary world.

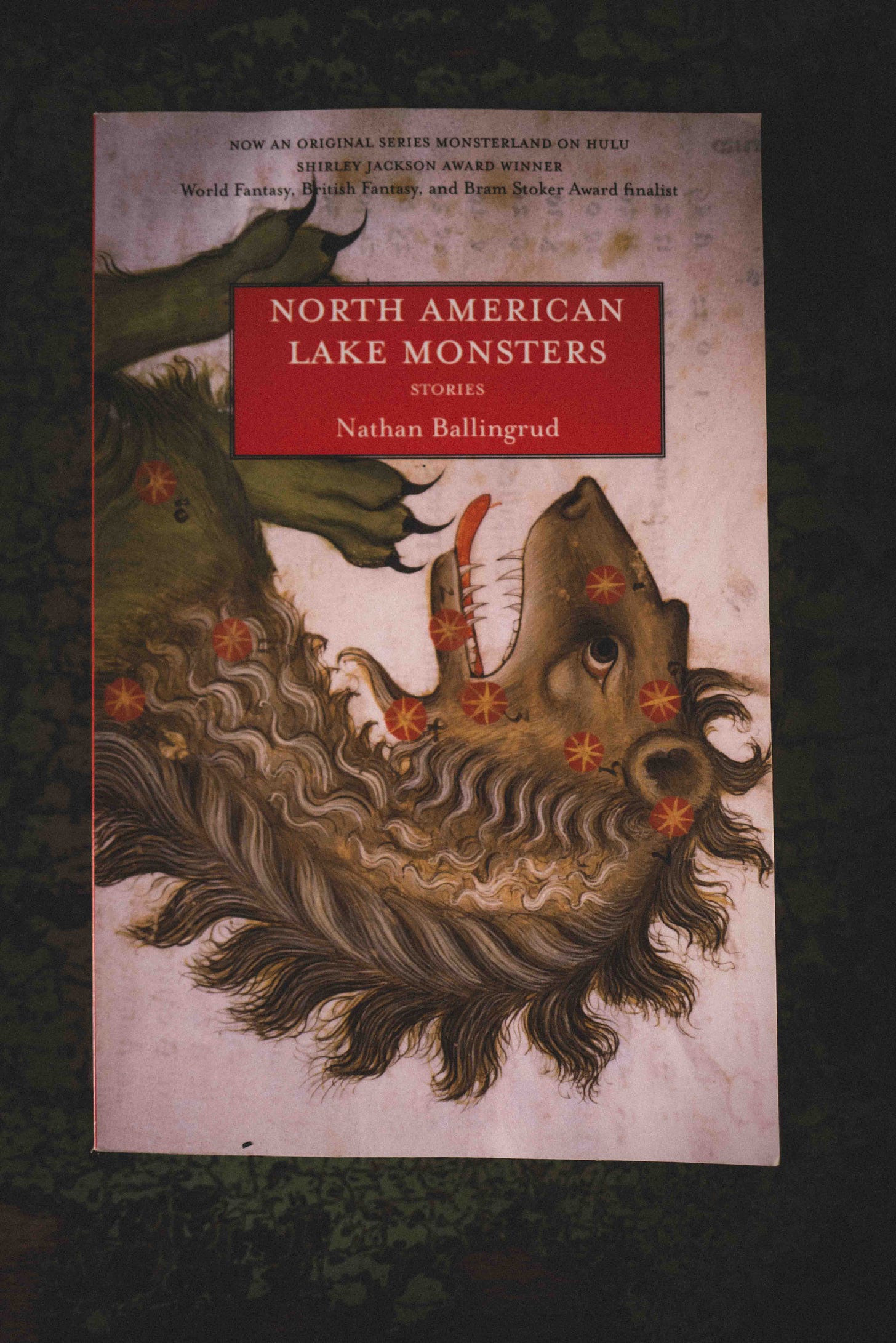

North American Lake Monsters by Nathan Ballingrud

Here’s an interesting little collection of stories! I read The Strange by Ballingrud last year, a nostalgic love letter to the sci-fis and Westerns of his childhood. This was a very different project. Each is an eerie tale featuring… you guessed it, a monster. But this is a more subtle book than that. There’s a darkness here beyond that of the supernatural, the darkness of the human heart, the monster within.

These are desolate stories about people pushed into difficult circumstances, either by structural neglect, abusive personal relationships, abandonments or harsh environments, all set in the American South. There’s a fatherless boy who becomes dangerously close to the vampire that lives under his house, the man just released from prison struggling to relinquish his tight control over his teenage daughter who takes it out on a lake monster, the couple who adopt a strange alien/angel in place of their missing son. Despite the difficult subject matter, Ballingrud exercises restraint throughout, perhaps too much. For the horror lover, you may be underwhelmed by this book. This is more horror adjacent, just tipping into that uncanny, disquieting zone of the not-real. This amount just about works for me. But for the psychological realism lover, I think this collection leaves just a touch to be desired. The tonality of the narration is much the same across the book, even over a wide range of different characters, which gave me a feeling of sameness. I also (thankfully) don’t think Ballingrud is quite depraved enough to give me a real hefty sense of the dark thought spirals some of these characters exist in. Or enough contrast perhaps, between their normal selves, versus the creeping darkness from their inner monsters.

Nonetheless I think this is a clever collection. I think the relationship between the monster and each of the protagonists of the story could be carefully teased out to good effect in each story. There is a subtlety, an elegance to Ballingrud’s work here which I like, but it just needs that extra something to push it into the truly great. I’ll definitely be reading whatever he writes next.

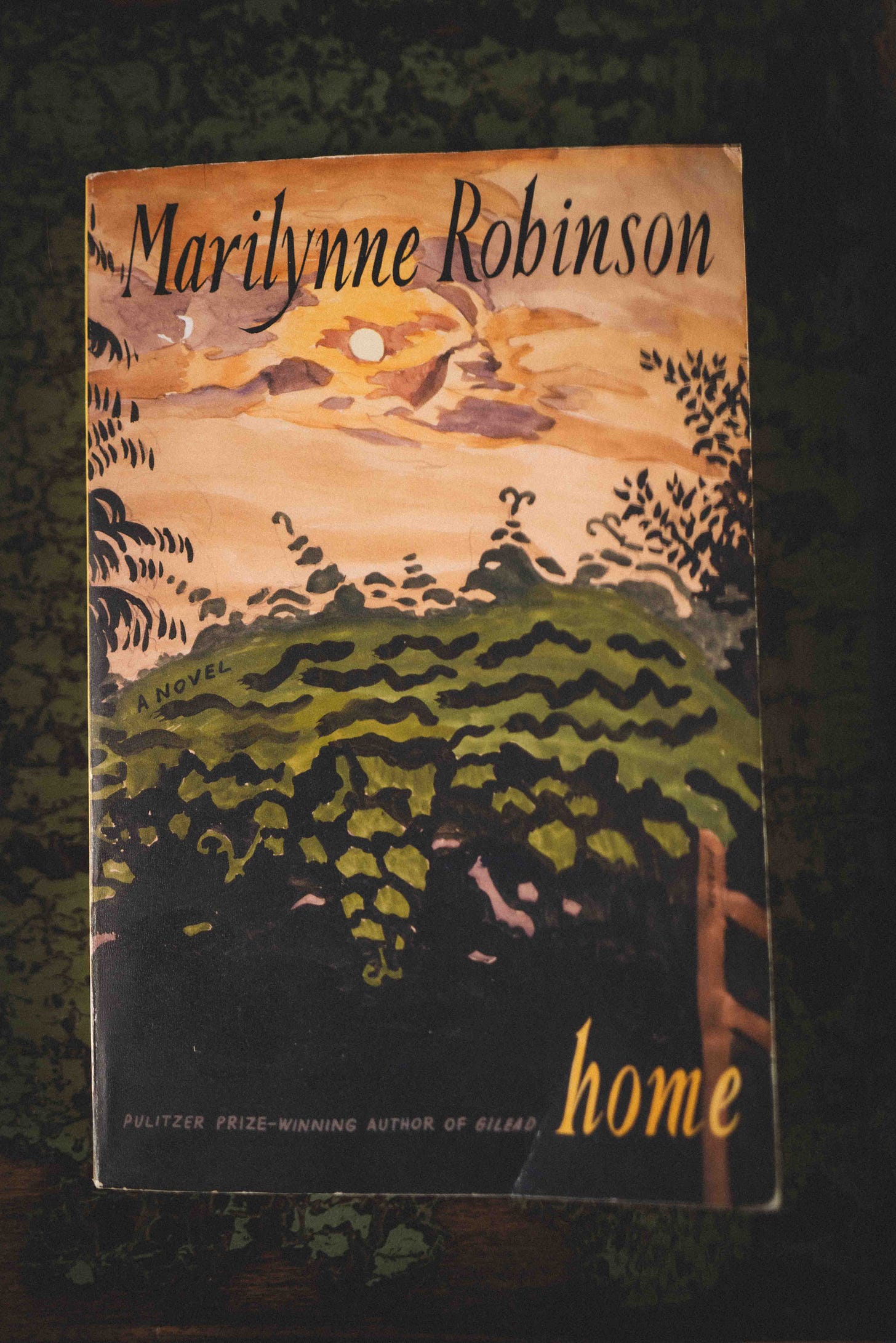

Home by Marilynne Robinson

You may already know that Gilead was another of my favourite books from last year, and I’ve been meaning to read Home for quite some time. The first novel is in epistolary form, letters written from the point of view of John Ames, a Congregationalist pastor living in the town of Gilead. He is writing to his son and trying to teach him his family history and also something of his sense of faith and how to live (East of Eden bells ringing, again). But he is also wrestling with the return to the town of Jack, his best friend the Reverend Boughton’s wayward son. Named after Ames and a thorn in his side, Ames struggles to find the forgiveness he knows he should afford Jack before he dies.

This novel, Home, takes us over to the Boughton’s place. It’s a third person narration but it’s mostly free indirect narrated through the eyes of the youngest daughter Glory, returned home after a painfully long engagement that went nowhere. When Jack comes home, the conversations between these two siblings reveal more about their lives, their souls. At the same time old Boughton is dying, and Jack tries to make peace with his father before he is gone.

This novel has all the hallmarks of Robinson’s mastery of her medium. She has great empathy for her characters, and a gift at bringing quiet, seemingly insignificant moments to life. Giving them the gravitas that they actually do have in the great sweeping narrative of our lives. It is beautiful in all the ways that Gilead was beautiful. People do bad things, they feel shame, they do good things, they feel better. That is the sway of this novel. How can we bear the movement between the two?

I think Gilead is the better novel, though. I felt the press of religion to be stronger in this one, interestingly. Whilst Jack has undoubtedly done some morally questionable things, he suffers an excess of shame in this novel for things which are perhaps not entirely his responsibility. Whilst there are hints, I don’t think Robinson quite unpicks the apparent necessity of Jack’s shame. I’m also not sure I know more of what’s going on here, or that this book advances the overall story, going over much of the same ground. I assume I’ll get more insight into Jack in Jack, but there was a lot of agonising here without enough forward motion, even psychologically if not plot-wise. The conversations between Glory and Jack, with all this high-minded discussion of faith and souls and how to live sometimes tipped into the unreal. They stopped feeling like fleshed out characters and became mouthpieces for ideas. Not always, but sometimes. I value the former in Robinson’s work so I was disappointed by it and at times grew a bit weary with the two of them. Gilead is a tauter novel.

My occasional qualms with it didn’t stop this novel’s ending from breaking my heart entirely. This was a painful one.

It feels like Robinson is working something out in these books. She is covering and re-covering the same ground, trying to squeeze out something important. I’m very intrigued as to how I’ll feel when I do get to the end of the series, and if I can make more sense of her intention here. Either way I still really enjoyed reading this, and look forward to the next.

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

As we come to the end of these reviews the theme for this month seems to be male protagonists asking how the hell they are supposed to live their life and do some good, when life is filled with so much pain? Addiction and faith link this one surprisingly to Home, in two otherwise very different novels. Many of the above have also been baggy and disordered novels, and this one is no exception.

We finish here with Cyrus Shams, an Iranian-American recently sober and trying to come to terms with life and the traumatic fact of losing his mother as a child in the Iran Air Flight 655 incident, where a commercial passenger plane was shot down by the US in 1988 (this really happened).

At one point Cyrus writes “We all have the snorting-spilled-coke-off-bathroom-tile-stories. That stuff is only interesting to those blessed with a rare cosmic remove from knowing actual addicts. Active addiction is an algorithm, a crushing sameness. The story is what comes after.” Indeed, here we have what comes after the long years of Cyrus’ addiction. Sure, we get some accounts of his life before, but mostly we get the sense of Cyrus’ raw newness in his sobriety, his wrestling with the fact that life, now, must go on. And his uncertainty of how to make that work. In the void made by the lack of drink and drugs, he latches onto the idea of martyrdom. He feels he’s been offered all this ‘extra’ life when he should have died, and so paradoxically he becomes obsessed with death. His mother’s death, the psychic death of his PTSD-ridden uncle, and the idea of the martyr, his desire to become a martyr and make his own death matter somehow.

The rawness of this novel is what makes it deeply lovable. It means that there are some odd and awkward moments, some cheesiness, but far more often there are some real transcendent sections because of its sheer vulnerability. Akbar himself is in recovery, and he writes from a place of deep empathy with Cyrus. That doesn’t make Cyrus always very likeable (and I think your enjoyment of the novel will lie in how much you like him and can tolerate what some would consider whininess). There is a juvenile, teenagery feel to this book which I think probably reflects some of what it means to be newly sober, fresh to the adult world once again. Especially for Cyrus, who has lost both of his parents by the time the story starts, and has had an unusual upbringing. Just being an Iranian-American brings its own baggage.

Akbar is a poet and you can see it here but not in the way you might expect. It is not lyrically and poetically written but instead you see it in his bringing together two seemingly opposite things and juxtaposing them in such a way as to make a striking image, and an important point. This book veers into all sorts of unusual territory. We have Cyrus’ poems about a range of martyrs (Bobby Sands, Bhagat Singh, his parents), interludes of his dreams where two wildly different figures might meet and talk (at one point we read a conversation between Lisa Simpson and his mother Roya), excerpts from the States’ report on the shooting down of Flight 655, first-person chapters from the point of view of Roya and her brother, the story of the Persian poet Ferdowsi. Of course all brought together by the central narrative of Cyrus trying to work it all out, it being life. I enjoyed the Cyrus part of the story, too, which was propulsive. It had its melodramatic elements, some corny dialogue which usually would make me wince. But honestly, I just really enjoyed it. I enjoyed reading it, I enjoyed thinking about it. I think it totally works because of the nature of what Akbar is doing here. It’s a wonderful, moving debut novel that will probably have you in tears by the end. I hope he writes more fiction!

And that’s everything for this month! I would love to know if you’ve read any of the above and what you thought of them.

For a full breakdown of everything we’re reading in book club this month, you can check out this post. Our main pick is My Death by Lisa Tuttle, which promises to be a fascinating, uncanny read.

Loved our East of Eden book club chat! We could have probably gone on for hours, there was so much to unpick with this one!

I think I had a very similar reading experience with That Old Ace in the Hole a few months ago. It wasn't the best Proulx but I really enjoyed it anyway. Even though it didn't read super smoothly, I can appreciate her wanting to give her characters space to just exist on the page, rather than have a specific narrative purpose. I think this is something that would have annoyed me a few years ago, but now I'm learning to enjoy it. I keep raving about one of her other novels, Barkskins, but it's just sooo good! I think you might really enjoy it. I need to read The Shipping News already. It's sat on my shelves for long enough!

I loved reading your East of Eden reflections - how funny we both read it this month! It is the perfect bookclub book, I have so many thoughts. I also felt such a challenging writing a review for it, as so much is going on. It is definitely highly flawed, I would agree, but ultimately really fun to get invested in. Cathy and her potential is nuance as to what she represents is something I have been thinking about constantly - i definitely think it’s there. She was so much fun - initially her characterisation horrified me, it was dripping in misogyny, and by the end I loved her and thought she was softened alot intentionally by Steinbeck. I also have so many thoughts about Lee - what did you think of him? I am equally super interested in Grapes of Wrath now!

Also appreciated your Martyr! review! It’s been raved about alot this year, I really want to read it. PS - how did you get hold of the US cover in the UK? The UK cover makes me want to hurl - and for that reason alone I have not read the book yet because I refuse.